An Intro to Videogame Design History

If you're interested in more research like this, most of it is going to be in video format over on the Forum's YouTube Channel. You can also support future work through the new Patreon campaign.

Also, you can now get the entire Reverse Design Series in print! The print editions are the definitive versions of the books. They are revised, profesionally edited, beautifully laid out, and expanded with new content.

This is the first section of a four-part essay on the history of videogame design. Originally the research for these articles began as a way to develop a new curriculum for game development students. The idea is that students of studio art, music, film, architecture and many other disciplines spend a lot of time learning about the history of their discipline. They gain a lot by that kind of study. It stands to reason that game design students might benefit by studying the evolution of their craft in a similar way. By first mastering the foundations of videogame design and then building upon those fundamentals, students can come out of their game design programs with a systematic understanding of videogame design: how it is done, how it began and where it is going. And so, to begin, we look back to the earliest days of videogame design.

Now I want to throw out a disclaimer here: this is meant as a theoretical history of videogames that explains broad trends in the evolution of game design. This theory does not attempt to explain the full history of videogames. There is a definite bias in this theory for mainstream games. Also, the theory is focused primarily upon console games until the late 1990s, at which point it applies to console and PC games more or less equally, although it still retains a mainstream bias.

The Arcade Era

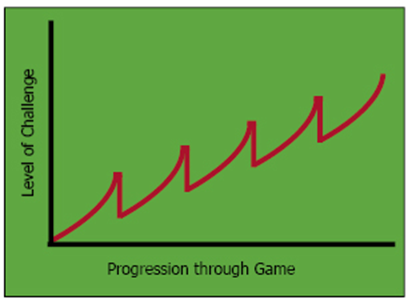

The core principles of videogame design were codified between 1978 and 1984. Videogames, as a form, go back much farther than that; there were videogames before even Pong came out, and those games had designers. But starting in 1978 it became clear to videogame creators that there were some ways in which videogames were very special. It was in 1978 that Tomohiro Nishikado’s Space Invaders became a worldwide sensation, introducing videogames to a whole generation of people who had largely not played them before. Space Invaders featured a new and engaging difficulty structure. Because of a small error in the way the machinery of the game was built, the enemy invaders became incrementally faster when there were fewer of them on screen. This meant that every level would get progressively more challenging as it neared the end. Nishikado didn’t originally intend for this to happen, but he found that an accelerating challenge made the game much more interesting, so he kept it. To add to this effect, he also designed each level to start of slightly more difficult than the last, by moving the invader fleet one row closer to the player at the start. You can visualize the game’s difficulty curve like this:

In a certain sense, this challenge structure is videogame design. Almost every videogame since Space Invaders has employed this structure in one way or another. Certainly, Nishikado’s contemporaries were quick to imitate and adapt this structure to their own games.

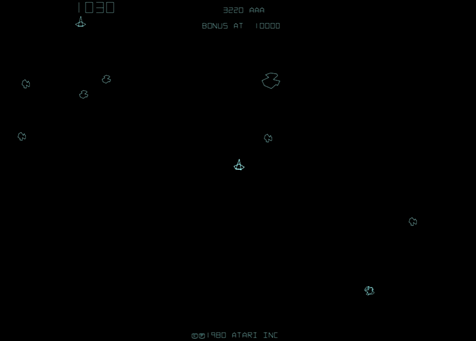

What designers of the era had discovered was that they could treat challenge as something that could go both up and down in a regular fashion, as though it were moving along an axis. We can refer to this axis as the axis of obstacles. (Obstacles being the things that stand between the player and victory.) At this point, the level of difficulty in a game corresponded directly to the challenge presented by the obstacles in a game. If a designer made the enemies faster or the pitfalls larger, the game became exactly that much harder, with essentially no mitigation from other elements in the game. It’s easy to plot an axis of obstacles for an arcade game, because they have so few variables. For example, in Asteroids, there’s really only one obstacle: the number of flying objects on screen.

To understand the axis of obstacles for Asteroids is to understand the design as a whole. This was a time when games were much simpler, from a design perspective, than they are now. Games would become more complex very quickly, however. The next industry-changing evolution toward contemporary games came in 1980, when Pac-Man was released.

The axis of abilities followed on the heels of the axis of obstacles, although in their earliest forms the two were nearly indistinguishable. If we think of the axis of obstacles as a range of challenges that can move up or down, we can say that the axis of abilities is a range of abilities for the player avatar than can grow, shrink or simply change. The foundational example is Pac-Man’s power-up. We’ve all seen this one:

When Pac-Man gets the power pellet, he gains new abilities temporarily. For a brief period of time, Pac-Man no longer has to run from the enemy ghosts but instead can chase them. Most people are familiar with this power-up and how it works; many are not familiar with its subtle nuances, however. Pac-Man’s design is actually full of movement along the axis of abilities. Pac-Man’s movement speed increases for the first five levels, and then starts to decrease after level 21. The speed of the ghosts that chase him, on the other hand, goes up and stays up. Additionally, the duration of the power pellet effect slowly decreases. If anything, Pac-Man’s movement along the axis of abilities is there to make the game harder, not easier. Yes, the power-up is a helpful, tactical tool, but the effectiveness of that power pellet decreases in sync with a decay in Pac-Man’s speed, making the (necessary) help you get out of it less and less meaningful. This is basically a back door into the axis of obstacles. By subtracting player abilities over time, Pac-Man gets harder in the exact same way it would if the obstacles were increased.

This use of the axis of abilities as a kind of back door into the axis of obstacles is one that was very popular early on. Many games imitated or modified Pac-Man’s use of power-ups, but none did so more clearly than Galaga. An ordinary if well-executed shooter, Galaga featured a very simple power-up. Using a relatively easy maneuver, players could get two ships instead of one.

By doubling the player’s shooting ability, the game becomes fractionally less difficult, as long as the player doesn’t lose the power-up. If there is a more obvious power-up than this one, I have not encountered it. The trend is clear: designers of the early 80s were using the axis of abilities as a supplemental way of controlling the level of challenge in a game. The differences between the effects of the axis of obstacles and the axis of abilities were few.

Although Pac-Man is credited with being the origin of the powerup, it was a young designer named Shigeru Miyamoto who made powerups what they are today. Miyamoto’s idea was to treat the power-up as a way of changing the gameplay qualitatively rather than just making it easier or harder. His first game, Donkey Kong, features a power-up which accomplishes this effectively: the hammer. Donkey Kong is clearly a platformer; most of the game is spent running, jumping and climbing across platforms while avoiding deadly obstacles. When Jump Man picks up the hammer, however, something very important happens—the game stops being a platformer and becomes an action game.

With the hammer in hand, Jump Man loses most of his platforming abilities like jumping and climbing, and instead gains an action game ability: attacking with a weapon. For the duration of the power-up, the game crosses genres. The big revelation here for game designers was that, although the hammer was little more than a distraction, players liked it. Miyamoto and his colleagues realized that the axis of abilities wasn’t just a way of making the game more or less difficult. The axis of abilities could be a way of bringing in design elements from other genres to expand the gameplay possibilities and entertainment value of videogames.

Miyamoto’s discovery that the axis of abilities could allow designers to cross genres for a more engaging game would lead to a huge explosion in popularity for these games. In 1985 a new era began in videogame design: the era of composite games.