Part 3: Later Development & Genre Innovation in the Composite Era

The composite design era lasted from 1985 until about 1998 or 1999, at which point a competing design philosophy emerged. That new philosophy, however, didn’t replace composite design as much as coexist with it. During those thirteen years, there were was a tremendous amount of innovative developments in videogame design. There are two important things to know about composite design in this period: one was that designers in different companies (and even countries) refined their composite design ideas, revealing a variety of techniques within the field of composite games. The second point, made on the second half of this page, is that even though composite games are essentially made up of two game genres that were created by someone else, they can still be quite original. We’ll see how the richness of composite design allows for these two things, from a historical perspective.

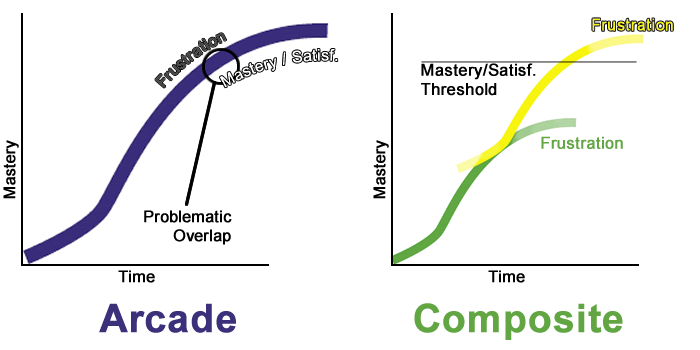

In the mid-to-late 1980s, designers all over the world latched onto composite design because they understood that it was easier for players to reach the mastery/satisfaction threshold in composite games than in arcade games. The mastery/satisfaction threshold is the point at which a player feels like they are satisfied and finished with a game, even if only temporarily. Although this point varies from player to player and game to game, I expect that every reader has experienced this threshold—or a lack of it. Consider how many fun, engrossing games feel incomplete even though the player reaches the end credits. Sometimes this can be the result of an incomplete story or major bugs, but more often it’s just that the mechanics of the game were engrossing but they never challenged players in a way that made them feel like they had achieved mastery. Or, consider the opposite: that there are many games that players put down before the credits, since they feel like they've seen everything the game has to offer them and mastered as much as they care to master. This happens when the player hits the "frustration point" before the game is technically over.

Most videogame designers know that the player’s takeaway impression of the game (and, therefore, the public's opinion of it) is going to be a reflection of the point at which that player leaves the game. The problem with arcade games was that they only focused on one or two skills, and so players often left the game at the point of frustration (burnout) rather than at the point of satisfaction (mastery).

Composite games helped to solve this problem. What you see here is that the point at which an arcade game satisfies its players also overlaps with the time at which players will simply get frustrated and stop throwing their quarters (and/or time) away, and simply leave the game dissatisfied. On the right hand side, however, you see how a composite game gets around this problem, by moving toward another genre when frustration looms. This is a simplified figure: a real composite game doesn’t switch from one genre to another halfway through the game. Rather, it bounces back and forth between genres throughout the game, but the aggregate effect is still the same. By honing skills from two or more genres instead of one, players don’t have to push through as long a frustration period to get to the mastery/satisfaction threshold. Instead, the game will naturally move them away from their current frustration to a new set of skills and then back again according to the rhythm of composite flow. Players still get the same satisfaction because they don’t view a composite game as delivering two incomplete curves; players think of their mastery of the game as a whole. The sum of those smaller skill curves still satisfies the player’s desire for overall mastery, while at the same time reducing the chances for frustration.

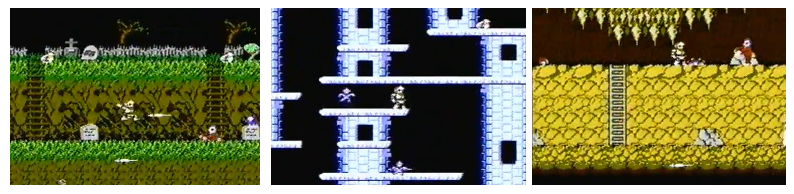

While many videogame designers realized how useful the composite game was in preventing frustration and enabling long-lasting fun, they nevertheless disagreed about how to implement composite design stylistically. There were two schools of thought on this issue in the NES era. On one side there were companies like Capcom and Konami who produced a series of hit games that were strongly reminiscent of the arcade era in their difficulty and design structure. These games were definitely composite games, but they employed composite design in a simple and binary way. One early Capcom hit, Ghosts and Goblins, takes the platform/shooter composite and immediately finds that back-and-forth rhythm.

In the middle you see what we’ve come to think of as a typical platform/shooter section, with multiple platforms full of patrolling enemies and jump-through floors. That level, however, is sandwiched between two sections (the levels before and after it) which seem almost like levels borrowed from an arcade shooter, with flat, parallel stretches. In those sections, the jumping only serves to avoid enemies. Indeed, the jumping in those levels has more in common with the evasive maneuvers of Space Invaders or Galaga than it does with the jumping in a Mario game. In this case the composite is very stark: the platforming levels are very focused on a single kind of forward-lunging jump executed with increasingly precise timing from different heights and angles. The shooter levels are all about using the jumping mechanics to help aim the player-character's shots, and avoid enemy attacks. Any given level could be pulled from an arcade game, so while it’s safe to say that Ghosts and Goblins is a composite game, it’s not very far removed from its arcade ancestors. Other games like Ninja Gaiden, Mega-Man, and Konami’s big hit Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles would reiterate this formula over and over again, focusing on steep mastery curves for one or two skills from each genre in the composite. These games did have considerable success, but they also turned off some audiences with a level of difficulty we now look back on with awe and/or consternation.

The other major school of design, obviously, was the one practiced by Nintendo. After all, it was Miyamoto’s discovery that powerups could do more than merely move the axis of obstacles up or down that led to the establishment of composite design. From Donkey Kong onward, Miyamoto and his peers at Nintendo focused on using powerups to shape the composite structures of their games. If a level in a game needed to shift from action to platforming, the designers would throw a bunch of platforming-themed powerups at the player character, and then let them use the abilities granted by those powerups in various pertinent challenges. For example, platforming-intense stages in Super Mario Bros 3 tend to feature more Raccoon tails than fire flowers, whereas action stages feature the reverse. The important thing was that not only did these powerups help to move between genres to achieve composite flow, but each emphasized different sub-skills within the active genre.

The powerups on the left, above, are some of the many from Super Mario Brothers 3. For the levels in which they appear, each of these emphasizes a certain skill in either action or platforming—although they all do at least a little bit of both. Nintendo designers realized, however, that inventing an exponentially increasing number of powerups wasn’t a sustainable design philosophy, and that it would eventually become impossible to improve upon their own games in this manner. Not long after Super Mario Brothers 3 and its many powerups, Super Mario World came out with essentially two primary powerups that encompassed all of the skills the designers wanted in the game.

This is where the development of composite design gets really interesting: starting around 1990 Nintendo and the rest of the market started to become more like one another. Designers outside Nintendo who had been experimenting in composite games saw that Nintendo’s games appealed to a huge audience. Some of this success was a result of Mario’s cultural penetration all over the world. Much of that success, though, was a result of game design. Nintendo used numerous, powerup-driven composite designs to make games whose skill curves were smaller and more approachable for new players. They also realized that too many powerups and/or core skills would deter parts of their audience as it might result in too many variations in skills, and be confusing. The result of this observation was that most mainstream games of the time had simplified control schemes built out of just a few powerups. You can this at work in later composite games like Yoshi’s Island and Mega Man X (and its sequels). Composite design had found a “happy medium” that lasted more or less until competitive multiplayer became a major driver of control schemes.

Now, if you have been reading and wondering whether all of this only applies to AAA Japanese games from the 90s, the answer is no. American composite games reveal another interesting aspect of composite design: combining two or more genres can, somehow, result in a new genre entirely.

The Problem of Invention

If designers of the 80s and 90s found the greatest success in combining two (or more) already-established arcade genres into one game, was it still possible for them to create truly original games? The answer depends on what you mean by originality. Designers found that even two games that had the same composited genres could be different. For example, A Link to the Past and Secret of Mana are both 2D, overhead action-RPGs with puzzle-oriented dungeons and a variety of long, involved boss fights. And yet, even though those two games came out for the same console within two years of each other, they are very different.

The difference is in the way that each of those games emphasizes different elements of the action, adventure and RPG genres of which they are composed. These games are great examples of innovation, in that they use old genres in new and exciting ways. That’s different from invention, however; invention means the creation of something completely new to the world. Gamers generally agree that entries in the Zelda and Mana series are both action RPGs in the same way that Sonic the Hedgehog and Super Mario games are clearly platformers. What really matters is not what genre those games are in, but how they fit together.

Just as we can learn things from by studying history of videogame design, however, we can learn things from the history of the gaming public’s opinions about genre. The first person shooter genre is generally considered its own distinct category, but FPSes came into being as a composite of the shooter, adventure and RPG genres. Public opinion is not always a reliable indicator of truth, but generally it’s true that our common uses of genre labels are meaningful. Someone looking for an RPG is probably going to be satisfied with a Zelda or Mana game, but someone looking for an FPS probably isn’t going to be happy with a side-scroller like UN Squadron, even though both games are shooters. First person shooters are clearly derived from their scrolling ancestors, but they’re not considered the same thing. Early first person shooters differentiated themselves by borrowing heavily from PC RPGs and adventure games. Consider the HUD of Doom 2.

That HUD is in place to give you information about your health, armor and ammo; it’s basically a set of RPG stats. Those stats don’t all increase like they would in an RPG, but they’re still complex and require close management. As for the adventure elements in Doom—how about all those secret passages and hidden alcoves? Modern shooters have largely lost the maze-like levels full of the hidden keys and switches that their ancestors had, but that was the way that early FPS levels were designed. If it weren’t for the adventure elements in the game, there would have been no levels to shoot through!

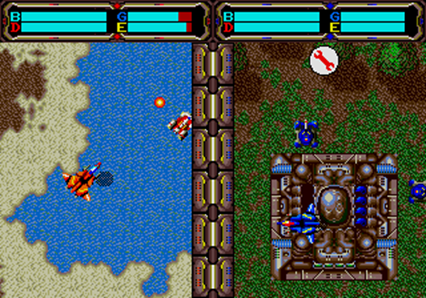

The real time strategy genre came into being in much the same way. Although we think of it as a distinct category now, it came out of numerous attempts to use a rich legacy of tabletop strategy ideas in a videogame context. Strategy games, much like RPGs, inherited a huge number of fully-developed game design ideas from decades of tabletop development. And as was the case with RPGs, PC game designers found that they could import these tabletop design ideas into their electronic games wholesale, resulting in videogames which very closely resembled their tabletop ancestors. These PC strategy games like Legionnaire and Eastern Front were obviously very appealing to people who enjoyed tabletop strategy, but not very popular outside that niche. Nevertheless, it was clear to designers of the late 80s and early 90s that there was a ton of potential in those strategy game ideas—they just needed tempering for mass market appeal. One of the first (relatively) successful attempts to make the strategy genre more accessible for the videogames audience was Herzog Zwei.

Many consider this game to be the first real time strategy game, and it’s true that it was a strategy game that added the exciting element of real time combat. If you were to play it, however, you’d quickly discover that it’s very different from the real time strategy games you know today. The reason is that Herzog Zwei is a composite of strategy games and overhead shooters (that plane you see in the image is not just a unit—it’s the player avatar) with a few economic elements included.

Herzog Zwei became a cult classic, but hardly popularized a new genre; it wasn’t until Dune II married strategic combat to full-fledged economic simulation that the RTS genre became what we know today. Economics is easily gamified, and so even in the 80s there were plenty of games that offered gamers a chance to play with money—everything from the ASCII graphics “Lemonade Stand” to the revolutionary Sim City. On top of its strategic elements, Dune II overlaid the economic HUD elements and god-mode perspective of games like Sim City and Populous.

The result was an engaging hybrid that felt qualitatively different from its parents. In RTS games like Dune II, the player can use economics and logistics (building a vast infrastructure and a huge army) to solve military problems (a more tactically skilled opponent). The reverse is also true: the player can use precise, efficient military action to make up for a scarcity of resources. That’s composite design in a nutshell. Like many composites that seem obvious in hindsight, the RTS turned out to be a very popular and enduring genre.

Although a new era in games began around 1999, the practice of composite design never really ended the way arcade design did. Indeed, it’s more appropriate to say that the next wave in game design (the set piece period) came to exist simultaneously with composite games. We still have composite games, and many of those games are considered original even though they’re basically composites of two already-established game types. Beloved, brilliantly innovative titles like Portal and Katamari Damacy are actually composite games. The practice of composite design is still very much alive, although it competes with other philosophies now. The point of going so in-depth with this article is that most of the important developments in videogame design as a whole happened in composite games between 1985 and 1999. The set-piece period—which we’ll look at next—changed many things, but it didn’t completely displace the practice of making composite games. Composite games are here to stay.