Part One Continued: Action Games and their Impact on Diablo 2

Diablo, the predecessor to Diablo 2, began its life as a fairly orthodox roguelike. While the project was still early in development, the main Blizzard team which oversaw the project told David Brevik that the game engine should work in real time. This decision changed the course of development in a big way, and introduced many important game design ideas that are not native to the roguelike subgenre. Because it started as a roguelike, Diablo’s relationship to its roguelike source material is fairly straightforward; it adapts roguelike concepts for a mass-market audience. The relationship between Diablo 2 and its action-game ancestors is more complicated and theoretical. One of Diablo 2’s greatest achievements is the way it recreates the fundamental structure of action games (Nishikado motion) through procedural means. This section will look at the action heritage of Diablo 2 and explain the way it reinterprets that heritage through an RPG lens.

One issue I want to tackle before looking at the history of the action RPG is how to define the level-up. Critics and fans have argued about the point at which an action game has enough RPG content that it becomes a true action RPG, instead of just being an action or action-adventure game. (David Brevik himself pondered this question in another interview [25] without coming to a conclusive answer.) For example, many question whether The Legend of Zelda games are really RPGs. I say that they are, because Link can gain more health, magic, strength, etc. over time. These gains are usually not connected to experience points, nor are they part of explicit “character levels,” but does that mean the game is not an RPG? For me, Zelda is still an RPG, because these things are still level-ups. A level-up is a permanent, periodic increase in the power of a player-character. When Link gains more heart containers, his maximum life is permanently increased, and that permanency makes it a level-up. When he gains the use of the Master Sword, it represents a significant increase in power over the starting sword, and he has it for the rest of the game. These gains are all connected to finding loot, but as we’ll see many more times in this book, loot is often the most important kind of level-up. Link makes one or more of these gains in every major dungeon. The period is simply measured in dungeons rather than being measured in EXP. Whether or not you agree, this definition is enormously important to the rest of this book.

The Birth of the Action RPG

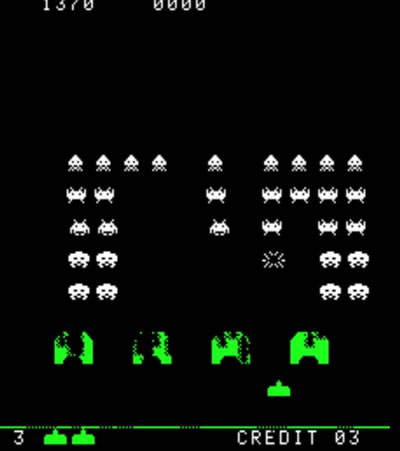

Once RPGs started to appear on PC and home videogame consoles, it was inevitable that design ideas would leak between the booming world of digital action games and the older world of tabletop RPGs. For designers of RPGs, this was a boon, for it gave them another way to escape from the overshadowing influence of D&D. For all of its systemic completeness, D&D never implemented the kind of real-time dexterity challenges found in action games like Space Invaders, Pac-Man or Galaga. (It’s difficult to imagine exactly how it could do so, to be fair.) By implementing action-game challenges against a background of RPG systems, designers could combine their favorite parts of RPGs with any of the various action subgenres. The result would be a hybrid game that felt significantly different from either of its parents. I call this the combination strategy, which allows designers to disguise relatively old RPG tropes in the clothes of an action game.

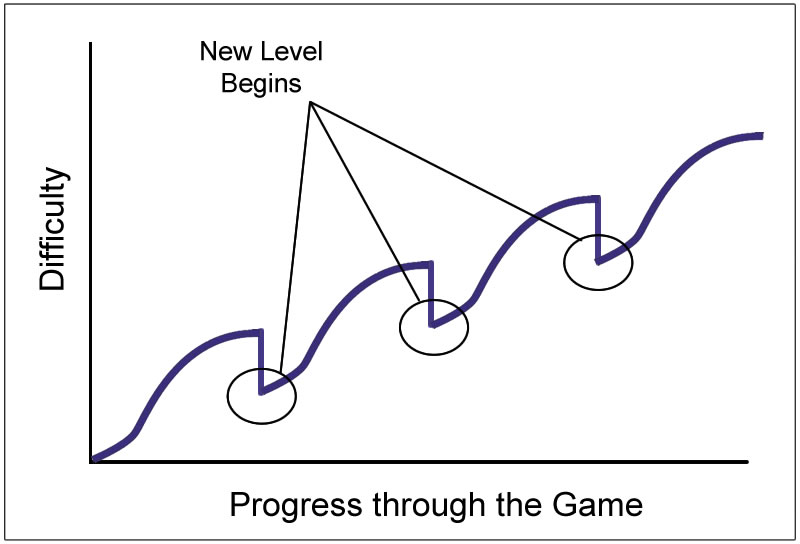

The combination of RPG and action is not only for the action gamer’s benefit, however. Designers often found that action game skills could be developed right alongside RPG stats over the course of a game. Demanding higher levels of thumb-skills from the player is a great way to defeat one of the RPG’s greatest problems: power creep. From the very beginning of RPG history, clever players have found ways to exploit the vast, interlocking systems of RPGs to become unstoppably powerful. That exploitation can be mitigated, however, if the player cannot execute many of the action-game skills required to take advantage of it. Diablo 2 isn’t designed to demand a ton of dexterity from its players, but they absolutely need better command of the action skillset to survive their first trip into the final difficulty setting. That said, what Diablo 2 really gains from action games is the revolutionary challenge curve which they invented. At its most fundamental level, Diablo 2’s difficulty structure looks more like that of an action game than that of an RPG, even though it leans more heavily on the latter genre in terms of mechanics and goals.

Two Difficulty Curves

The first game that is still relevant to the history of action game design is Space Invaders (1978). The designer of that game, Tomohiro Nishikado, was also the engineer responsible for the construction of its arcade machinery. Because of an error in the way he configured the game’s chipset, the enemy aliens move faster when there are fewer of them on screen.

This causes each level in the game to become more difficult as the player progresses through it. Rather than correct this error, Nishikado kept it as a design feature. Indeed, he embellished it by making each successive level start at a slightly higher level of difficulty, thus reiterating his serendipitous difficulty structure at the macro level.

I call this up-and-down motion in videogame design Nishikado motion. Nishikado motion is the fundamental structure that underpins nearly all of mainstream videogame design. Even today in the era of extensive player psychology research and interest-curve diagrams, Nishikado motion remains the central pillar of mainstream videogame design.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions.

Character Classes - Back | Next - Randomness in Diablo 2