Extra-Thematic Levels: Mini-Theme & Isolated Concepts

Mini-Theme: Vertical Levels (Vanilla Secret 1, Gnarly)

Even excluding water levels, there are more than a few sections in Super Mario World that feature vertical progression, where Mario has to go upwards instead towards a goal of moving left to right. Weíve already covered the levels that feature a fence-like mesh, mostly as sub-sections of the periodic enemies theme. Generally, those levels donít do anything interesting. Part of the problem with vertical levels may be that the mechanics of the game allow only a small amount of possible content. Compared to its historical peers, Super Mario World was overflowing with game mechanics, enemies, environments and player abilities. That said, the design team did a good job keeping Super Mario World from becoming too bloated with mechanics. The vertical levels in Super Mario World show where the design team scraped up against the edges of their design, and this mini-theme (as it were) shows it. The two levels in this mini-theme are Vanilla Secret 1 and Gnarly, which have a lot in common. The second half of Mortonís castle is also a vertical climb, but it fits into the moving targets theme very well, and has little in common with the two levels analyzed below.

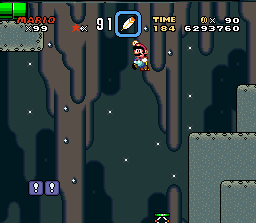

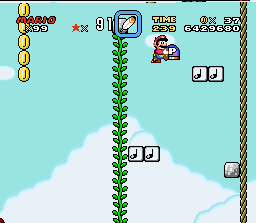

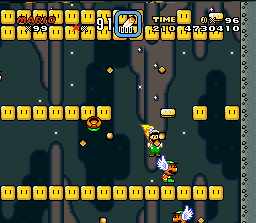

What the design team found in vertical levels is that they make for interesting open mazes. By this I mean that in both these levels there arenít too many walls, because gravity does the work of a wall in preventing Mario from reaching certain parts of the level. The best example of this in Vanilla Secret 1 is this section, where the player needs to move a springboard to the right location in order to access an obvious but distant pipe.

As it is in many other places, itís possible for an experienced player to ďcheatĒ with the cape and reach this without the springboard, although itís one of the harder game-breakers to perform, because the platform is so short. Springboarding from the high platform wonít work because of the ceiling, and it wonít work from the other platforms available as they are too far below. A big part of this puzzle is merely realizing that it is a puzzle, and that springboard placement is the key. Of course, this requires that the player has completed the Blue Switch Palace. Itís rare for a level to require a switch palace other than its native one (i.e. yellow for Yoshiís Island, red for Vanilla Dome). Star World 5 does the same, although both instances can be circumvented by flying. Still, itís an odd choice, which makes me wonder if this level was one of the last to be made; certainly, the unusual puzzle aspects would make sense in that scenario.

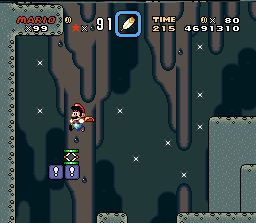

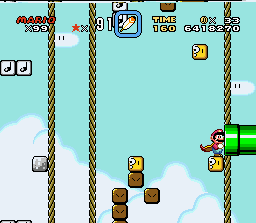

Gnarly does more than Vanilla Secret 1, as it should considering its position in the game, but it also shows the limits of what the designers could do with vertical design in this game. In Vanilla Secret 1 there are climbable vines, springboards of various kinds and plenty of patrolling Wing Koopas. Gnarly uses plenty of springboards and adds the motorized rope but it doesnít do a ton with either of those things. The really interesting things all happen in the vines. These four vines actually contain a puzzle.

By destroying this block, the second vine can climb significantly higher, leading to an extra life. This is an interesting puzzle, and uses all elements which are already familiar to the player. Itís an easy intuitive leap to figure this puzzle out, but only once the player has actually seen the area where the puzzle takes place. Thereís nothing a player can do to refresh the vines in this level (although going into a pipe would reset the vines if it were an option), and so the puzzle is a one-time offer, at least per level. Certainly, the designers could have inserted some kind of reset button unique to this level, or offered a pipe loop at the bottom of the level. The first option, though, would involve the designers adding largely superfluous mechanics, which isnít something Nintendoís team did too often in the early 90s. The second option would involve dropping all the way back to the bottom of the level on every puzzle attempt, which is also something that doesnít fit with the design teamís style. Essentially, the designers could have done more with the vine puzzle here, but not without changing their game in a larger way, and so they simply obeyed the established borders of their design.

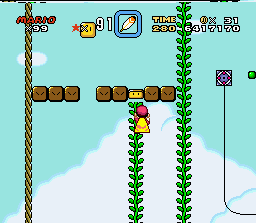

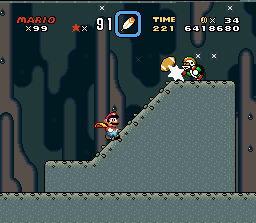

The second puzzle is similar in that it involves a common level design element elaborated in an unusual way. In order to access the hidden Yoshi Coins for this level, as well as several hidden extra lives, the player has to find a way to ferry this P-Block up to the divider in the level to take advantage of the short timer and enter the otherwise inaccessible pipe.

Itís not an easy set of jumps because of the narrow landing and enhanced momentum, but a cape helps. The only real criticism I have of this puzzle is that this is one of the least-known secrets in Super Mario World, because the P-block is so far away (in terms of the time it takes to navigate the tricky jumps) from the part of level it meaningfully modifies. That said, if there is an appropriate place for complicated, atypical puzzles, the Special zone is it. Itís not a repeatable lesson that would work in modern games (how easy is it to just Google these things, these days?), but it does adhere to the design principles of the game, so it deserves mention.

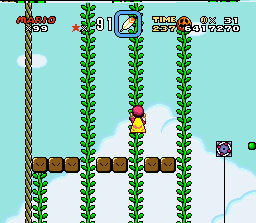

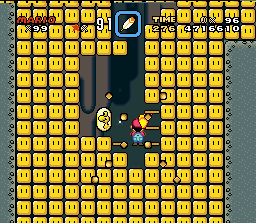

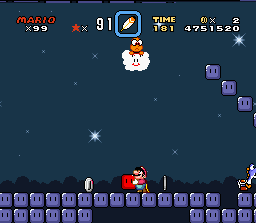

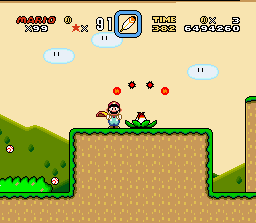

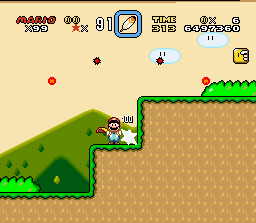

In both cases, the player ends the level by facing off against an enemy in a raised position that hurls intercepts. Itís plausible that this is a coincidence, or a product of general principles that the design team was following during the project. My theory, however, is that these levels were designed alike because one is a direct evolution of the other, along (mini) thematic lines.

One last note on this mini-theme: I donít just group these levels together because they are vertical and employ a few of the same tricks. They also both end with an oddly similar challenge. You can see what I mean here:

Irregular Levels: Isolated Concepts

STAR WORLD 1

One of the things we've seen several times in this analysis of Super Mario World is the technique of rewarding the player with easy fun. Obviously, this is a game, and so the whole thing is supposed to be fun. It's also not a niche game, so the whole thing is supposed to be fairly easy. But ease and fun are both relative concepts here. Star World 1 conveys a sense of what we might call ďsillinessĒ in gaming, a feeling which arises out of a minimal amount of danger. Danger is essential to a platformer; that is to say, without some risk, the game isnít a game. Obviously, there can be too much danger so that the playing of the game feels withering, especially to first-timers. Anything short of that kind of abrupt discouragement can be fun. Indeed, sometimes the closer a level comes to this level of frustration (without actually being so), the more fun it is to beat that level. But at other times, itís nice to play a level thatís tame and short, and only has enough danger to keep the playerís attention.

Star World 1 has no bottomless pits. It has few enemies, and all of them are eminently avoidable. It offers numerous powerups, coins and the opportunity for extra lives. And all of the level is navigated by ridiculously long chains of spin jumps. Itís also got the most super stars of any level, and theyíre all close to one another. Itís a kind of bonanza, where the player can indulge several ďwhat-if?Ē impulses at once.

The artistry in this level isnít merely that itís a silly level with a jackpot of powerups located at the bottom. The artistry is in the levelís placement in the game. Nearly a quarter century of exposure (and, more recently, the existence of YouTube) has obliterated all of the gameís secrets. Once upon a time, though, a player would have been pretty proud of discovering the Star Road, and felt perhaps both relieved and somewhat tired after the effort. It might have been doubly so because the fight with Big Boo was abnormally placed. This level, with its lighthearted gameplay makes the perfect denouement to that tension.

STAR WORLD 3

Star World 3 does something that seems totally commonplace to players and designers today, but which was actually rather unusual back then. Star World 3 features a one-challenge level. In the age of casual games, online flash arcades and indie niche titles, a one-challenge level is a part of the design vocabulary. It makes sense, too: why not break up levels into obviously discrete chunks which can be digested in small sessions? It also works for skill development via repetition, as itís quick to load and quick to retry.

This level looks exactly like the kind of phenomenon described above, and it operates similarly, too. Here, the playerís goal is to get into Lakituís cloud by knocking him out of it with a kicked block.

This is a skill which is very specific and rarely used, and therefore perfect for a one-challenge level. This challenge reflects upon the game as a whole in a really meaningful way, though: each individual skill in Super Mario World is useful in so many different contexts. Consider how many contexts there are for the back jump, the cape glide, the limited height jump and so on. Part of the way that players remember a game is by playing it again and seeing how far their skills have come. The ability to overcome challenges in the game using several different skills in improvisatory combinations makes Super Mario World feel like a world with its own rules rather than just a game that can be solved algebraically. Much of the magic of videogames, and the way that they differ from analog games, is in the wholeness of the world. Because a videogame like Super Mario World is so filled with the possibility to improvise, modify and wander, the game feels incredibly coherent and wonderfully complete. The interchangeable (but not equivalent) skills are the feelers which transmit this completeness to a player.

This is not to disparage short levels or discrete modules of content; they definitely have their place in game design, platformers and even in this game. Itís just that Super Mario World is doing something very different, and playing this level after playing all the others illustrates how different it is.

DONUT PLAINS 1

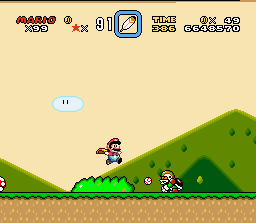

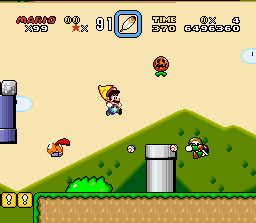

Donut Plains 1 features a number of challenges that do not fit neatly into any of our classifications. We donít really see a standard progression of evolutions, expansions and so on, although the challenges do change across the course of the level. Principally, this is because Donut Plains 1 has more in common with the gameís first two levels than it does with any of the rest. The goal of this level is to show the player how to use the cape powerup, and so we see some great tutorial challenges and a steady back-and-forth composite rhythm. The level begins by forcing the player to fly. Leaping to avoid the projectiles from the first Pitching Chuck will lead to this:

Much like in Yoshiís Island 2, thereís a lot of extra space for the player to run through before the next challenge. The difference here is that this space allows Mario to easily gain enough speed that any jump will cause cape-flight. The Pitching Chuck presents a hazard that requires a jump, and therefore the designers ďtrickĒ the player into flight. Naturally, the design team has placed a platform in the sky that confirms the propriety of the soaring leap, and shows that cape-flights can often be rewarding and fun. The level is actually filled with extra opportunities to do the same, although the design team doesnít really go out of their way to coerce the player into flight as they do here. This idea also doesnít really develop across the course of the level, which is why this level isnít included in a theme.

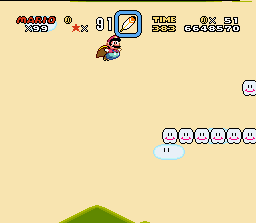

The designers spend the rest of the level reinforcing the many other basic skills associated with the cape. For example, the level declines sharply toward action in these two spots, featuring the Volcano Lotus.

The arc of the Lotusís fireballs precludes all but full-momentum cape-jumps, which arenít easily possible in either location without foreknowledge of the challenge and a concrete plan. What the player is forced into doing is using the lateral cape attack. This, obviously, is a key skill that the player will need to know to use the cape in action situations throughout the rest of the game, although this is a very limited, introductory context for the skill.

This level also does a great job of isolating the most common cape-based skill: the gliding descent. Because of the way jumping to max height works (the player has to hold the jump button, which is the same technique for gliding), cape gliding is very intuitive and will happen before these challenges. What the designers do is to expose the player to the specific context for more nuanced cape glides. The first example is here:

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions.