The Preservation of Momentum Theme

The preservation of momentum skill theme is all about putting Mario in situations where it would be best to get out quickly, and then slowly making that escape more and more difficult. The stats on this theme are exactly what one would expect. This theme features the biggest average d-distance and the largest delta height, both of which make sense given the qualitative aspects of the theme. Because Mario needs to keep up his momentum to get through challenges quickly, that same momentum is going to make it easier for him to gain critical height and distance on his jumps. Moreover, this means that if the player doesnít keep up Marioís momentum, it will greatly endanger him. This negative feedback loop is a key part of this theme. Obviously, Mario can regain momentum, and this game is rarely very difficult, but the onus on speed in this theme is very different from the focus of other themes. Both the periodic enemies and moving targets themes have as their core skill the timing jump, in which waiting in a relatively safe place is common. As for intercepts, even when those intercepts damage Mario, many are only a threat for an instant. Now, these ďspikesĒ in difficulty are relative to a fairly easy game. But as weíll see throughout the theme, even when Mario isnít faced with a 2-penalty pitfall or the like, challenges can get (relatively) more difficult all of a sudden. Itís not the difficulty thatís important, but rather the sudden change in it stemming from lost momentum.

Like its fellow on the platforming side of the composite, the preservation of momentum theme is heavy on iteration and somewhat light on accumulation. Only the pinnacle level, Awesome, demonstrates level-wide accumulation. But the iterations in this theme are a lot more appreciable for the player than they are in the moving targets theme, because of how different they all look and feelóeven if the underlying mechanics of each level arenít that different. That difference in feel stems from the feedback that drives the player: thereís always some glaring reason to keep moving. The theme begins this with sinking platforms in Yoshiís Island 4.

Although theyíre hardly any danger, the sinking action of these platforms will keep the player moving forward by simple, safe necessity. Skipping ahead a bit a similar thing occurs in Star World 5, which features a long gauntlet of falling platforms too. These two levels are not close to each other chronologically, but itís interesting that they are two out of only three levels in the game to make use of the traditional sinking/falling platform in a fully developed cadence. Falling or sinking platforms were, up to this point in Mario history, a staple of the game; they appear infrequently and only in greatly altered forms here.

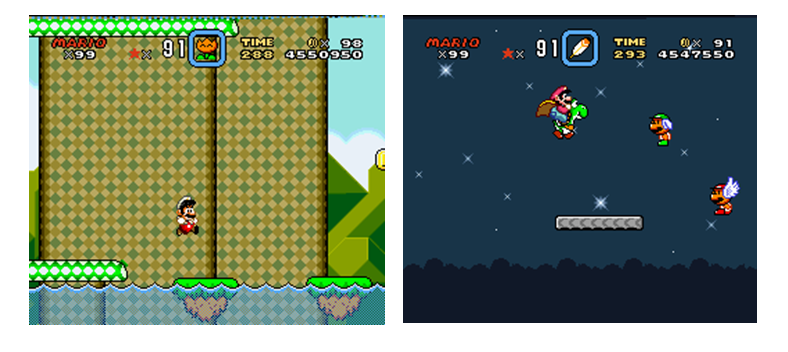

This change makes sense when looking at the rest of the levels, because the designers had no problem implementing other reasons for Mario to keep going. In Donut Plains 4, the player faces rising pipes and lots of overhead intercept enemies.

This level is actually the first to introduce overhead intercepts, and it does so outside the intercepts theme. (This is the only time this happens.) But both the extending pipes and Hammer Brothers give Mario excellent reasons to keep going. The former requires momentum to gain the proper height and beat the full extension of the pipe, and the latter involves a relatively dangerous enemy whose death is unnecessary, grants no reward, and is just as easily bypassed as fought. Add to that the endlessly falling enemies in the second half of the level, and it becomes very clear to the player that itís best to run rather than fight.

Mounting danger is the single most-used design idea for pushing Mario through challenges at high speed. In particular, enemies that spawn periodic projectiles in a confined setting make for challenges that are best attempted without stopping. That is to say, timing isnít the core skill, or else these would be periodic enemy challenges. At first, this is very clear. Forest of Illusion 4 brings back the extending pipe, but this time also throws in the hovering Lakitu who will rain down Spikey enemies constantly. Lakitus dwelling in the pipes do this too.

The Spikey enemy isnít invincible, but it is harder to kill than a normal enemy, and so itís better for Mario to just flee. The high and/or extending pipes and Lakitus just make jumping with momentum a greater necessity. Some of this carries over into Chocolate Secret and Valley of Bowser 4, which both feature projectile-launching Chucks.

The reason this isnít a periodic enemy challenge is thereís no timing jump or short, well-timed run which solve the essential problem. In each case Mario is vulnerable to the projectile until he gets through the whole challenge, and each challenge is fairly wide. So while timing certainly helps the player to begin a challenge, itís the skill of keeping up Marioís momentum with reflexes and ďreading aheadĒ in the terrain that carry the player to victory.

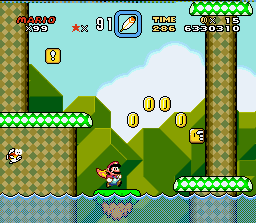

Now the most prevalent trend in this theme is that Marioís momentum must be maintained even while it becomes harder and harder to do so because of obstacles of increasing complexity. The pinnacle for the theme turns this on its head by making it almost impossible to stop Marioís momentum. The level in question is Awesome, which uses icy platforms that preserve Marioís momentum even when the player doesnít want it. This icy terrain first appears in Donut Secret 2, which is vastly simpler than Awesome even if the basic ideas are the same throughout.

Many of the challenges in this level look like they would be rather easy except for the icy terrain which makes control of Marioís momentum more difficult. This highlights the core skill of the theme; it isnít about merely rushing headlong into every situation, itís about controlling Marioís momentum. Itís easy to get Mario running, but controlling that momentum precisely is what this theme is all about, because messing up a key jump with full momentum will bring on the negative feedback loop as much as a lack of momentum will. Awesome really hammers this home in the second half of the level. This section is the themeís big accumulation, combining mounting waves of enemies with the icy platforms.

The combination is toughónot only does the player have to deal with a really large number of enemies that form walls of damage around Mario when he stops, but the player has to do it with less control of Marioís momentum. In other words, the player really needs to be able to think ahead because small miscalculations will become big problems in this level very quickly. Really, this is one of the more frustrating accumulations in a theme, but it does definitely rely on skills taught by the rest of the levels.

YOSHI'S ISLAND 4

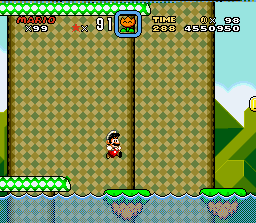

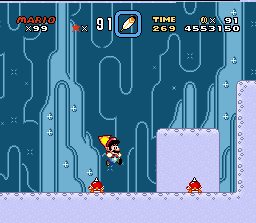

Like most of the skill themes, the preservation of momentum theme begins with the training-wheels challenge. Unlike the other themes that do this, though, the preservation of momentum theme has a problem: it has to convince the player to keep Mario moving. In order to force the playerís hand, an element of danger has to be introduced; avoiding that danger keeps Mario moving. Still, a training-wheels challenge only lives up to its name if removes the penalty, simplifies the action and softens the danger. This challenge does a good job of accomplishing everything in one go.

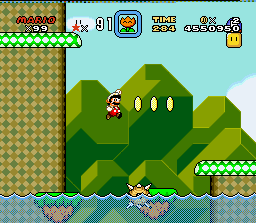

These platforms slowly sink into the water as Mario stands on them. The player will, eventually, react to this by jumping off the platform and onto dry land. The incentive to jump off the platform quickly and keep Marioís momentum moving forward is obvious. Yet, the danger of the challenge is mostly negated because of the water below the platform. Even if the player waits and sinks, Mario wonít lose a life immediately. Thus, these challenges work perfectly to show the player the value of preserving Marioís forward momentum and preserve an inexperienced playerís small stockpile of lives with an unconventional set of training-wheels.

The second challenge is the standard challenge for the level: two sinking platforms in sequence. While swimming in the water is possible, itís slow and boring. Jumping on both of these platforms is funóbut the player needs to be quick about it, even if failing isnít fatal. Itís a lesson handily learned by even inexperienced players, and so the evolutions start immediately after this challenge.

Here you can see the first proper intercepts of the level, but itís important to recognize that one of those intercepts is actually not a danger at all. The left spike ball floats harmlessly under the dry-land platform, serving as a good warning shot that alerts the player of the spike ball which will intercept Mario on the upcoming challenge. For the preservation of momentum and intercepts themes, fast reactions and speedy ďreadsĒ of the terrain are essential skills. New players arenít going to be very far along in developing those skillsóindeed they may not even be aware of the possibility of this kind of interceptóand so this warning shot alerts them to it.

After this there is a bridge challenge, although itís a very rudimentary one. Technically the bridge created by the p-block is a crossover, because it takes the emphasis off platforming and places it on action as Marioís goal is to shoot a shell through several enemies. I call it rudimentary because this crossover involves action but doesnít really belong to any skill theme; there are no intercepts, or significant periodic movements by enemies, or moving platforms. Obviously, this is forgivable because itís such an early level, but pointing out what this challenge lacks is at least useful in helping to negatively define skill themes and bridge challenges, generally. There is one thing to give the designers credit for: this challenge breaks up the rest of the platform jumps rather nicely without sacrificing the underlying training-wheels (water) or asking the player to do too much.

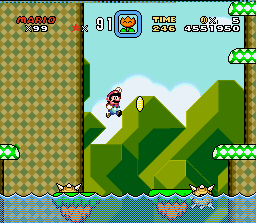

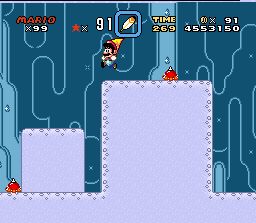

After the bridge, the levelís main sequence begins with a basic expansion. Whereas there were two sinking platforms and one spiky ball, this is expanded to two intercepts, although the second intercept is actually travelling slower than all the rest in the level.

Again, this stems from a desire to make it easier on the players who are seeing their first expansion in the theme. Next there are three platforms and three intercepts, yet another expansion. The intercepts have all increased, as have the number of sinking platforms, but what hasnít increased is the d-distances between these platforms. Three identical jumps of this kind are not mechanically more difficult than two identical jumps, but to a new player it can be psychologically more taxing. This is yet another example of positive deception on the behalf of the designersósomething which we will see a lot in this theme.

Finally, there is a mutation challenge that illustrates one of the aspects of mutations which bears considerable study. This leaping fish stands in for the spiky intercepts of the previous challenges; naturally, it is different in appearance and behavior than the obstacle it replaces, but the kind of difference is important.

The jump this fish forces Mario to take is only slightly different. Itís a little higher and a little narrower as well. Momentum-wise, thereís no change. In essence, this jump is calibrated so that itís no more difficult than the standard challenge, and indeed the skill the player is using is the same skill. What the mutation jump does best is to force the player to explore more of the nuances of a skill theyíre already using comfortably, without necessarily demanding more of their skills to create that feeling of dominance without sacrificing knowledge gain. The way this jump controls for angle while maintaining virtually every other variable is a great example of how mutations are done, when theyíre done well.

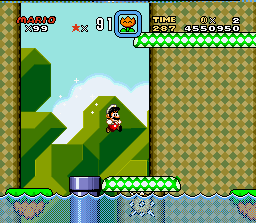

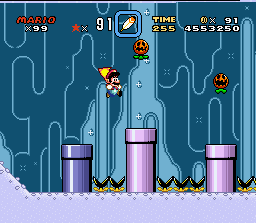

DONUT SECRET 2

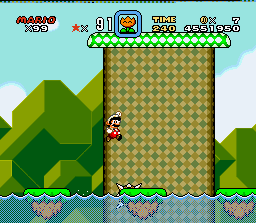

The designers of Super Mario World, either by accident or because they knew and accepted the major flaw of the cape powerup, put in place numerous levels which force the player to use aspects of the cape that donít involve sustained flight. Donut Secret 2 is one of the cleverer levels of this type. As I noted in section II, Super Mario World gets rid of the turn-and-slide mechanic present in SMB and SMB3. When Mario reverses course in Super Mario World, no matter how strong his momentum is, he will go in the new direction instantly so long as he is on the ground. This level does away with the new stop-on-a-dime mechanics and goes toward the other extreme. Everything is covered in ice, creating a low-friction surface that makes it much harder to reverse course quickly. Mario veterans will resort to the momentum-breaking jump that was so essential in earlier titles; new players will be learning that and a few other skills both essential and specific to the cape powerup. Essentially, what this level is out to do is force the player to use momentum-controlling (rather than momentum-halting) skills by taking away Marioís ability to stop.

Often, levels that undermine one of a gameís fundamental mechanics (like being able to stop) can be terribly mean-spirited and generally disliked. It doesnít make sense to teach your players to expect something and then take it away for spite. Donut Secret 2 gets away with it because of how well-placed all the levelís obstacles are. Players canít halt Marioís momentum, but they donít need to.

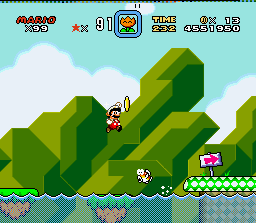

The spaces where Mario is supposed to land and then jump again are obvious. The key is that not only does Mario have to jump in the right places, but he needs to work with the icy momentum to get to the top of the high cliff and avoid the enemies. Combat is possible with the cape, but that will send Mario into a wall, breaking his momentum and causing him to have to start back along the slippery terrain away from his destination.

One thing that will help in almost all the jumps is a cape glide, which can give an airborne Mario the few moments the player needs to plan out the next few actions. Cape glides also help to preserve momentum where itís especially useful, as in the case below.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions.