Acceleration Flow: Part 1

“It’s not about items, is it? You don’t really care if your new crystal nethersword is going to clash with your new elite boss clogs. It’s about the numbers. You want the items with the best numbers so you can use your numbers to decrease the enemy’s numbers until your numbers are the best in the land [...] No one ever ruined their lives to get 100% completion in Super Metroid.”

-Yahtzee, Zero Punctuation Reviews: World of Warcraft Cataclysm

Why is it fun to level up? Many readers will have seen or heard the recent discussion going on about a “Skinner box” technique, and all the abuses of it that have emerged in social media and other recent games. Is a level-up system just a psychological trick used by developers to ensnare gamers in un-fun games? In a word, no. There are many good, honest and genuinely fun level-up systems out there, and there are many good reasons for why we like them. One very important reason is a phenomenon I call acceleration flow. Acceleration flow has much the same engaging, euphoric effect as the more traditional flow, but its causes and conditions are unique to level-up systems.

Acceleration flow is easily illustrated--in broad strokes--in a very famous context: World of Warcraft. As the headnote to this piece explains rather humorously, the reason that people play the endgame of WoW seems paradoxical to outsiders. They play endgame raids to acquire powerful gear, and they use that powerful gear to play endgame raids. Where’s the payoff? One easy answer is that gamers want to be the best; fame is a real thing in WoW. But only one group can be the best, and more than that, not everyone wants to be the best. Indeed, most people realize it’s never going to happen. And yet they keep playing. So what attracts them to the game? Socialization? Perhaps a little bit; it can be fun to play with 24 other people, sometimes. But if you’re looking just for socialization, World of Warcraft is definitely not your first choice. So what keeps people doing the endless loop of gear for raids and raids for gear?

The secret behind the allure of this endless loop is the possibility of the acceleration of power. For each piece of gear that a WoW player gets from a raid, the game becomes a little bit easier. The bosses that drop the next piece of gear fall a little bit faster. Not only is the player character getting progressively more powerful with each piece of gear, but that gear is helping them to grow more powerful, faster. The rate itself at which the player character grows more powerful increases. A positive feedback loop is in effect, heading toward what the player infers to be a singularity: the point they become an ever-growing unstoppable force.

This feeling of accelerating power is extremely exciting; in fact, it is very similar to the feeling of flow. The person experiencing a traditional flow state is not thinking about what they’re doing; they’re just acting and enjoying seamlessly, in an almost hypnotic way. Players who are entering an acceleration phase in a level-up system feel something analogous. They’re not thinking about the tedious repetitions they have to perform in order to level up, they’re just doing them, and enjoying the accelerating rate of the results. What’s different is that players in a level-up acceleration aren’t in that hypnotic state. Rather, those players are caught up in a future in which their character(s) will be powerful in a way they can’t even understand yet. To put it more technically, they’re inferring an exponentially increasing power structure that vanishes beyond their player prediction horizon. It’s not exactly the same as traditional flow, but the exhilaration of the players is subjectively very similar.

Of course, I described a simplified version of the process of attaining equippable gear at the maximum player character level in World of Warcraft. One might object that this is not leveling up, or is too specific to one game. If I were to describe it in different but equivalent terms, the distinction would vanish. “It’s a process in which players spend time defeating enemies and completing tasks to gain permanent power upgrades.” Is the previous sentence describing leveling up, or getting gear? Gear is permanent in the same way that leveled “stats” are. Having 37 agility helps you in combat--helps you in perform combat and other tasks until you level up and have 38 agility. Having a helmet that gives you +37 agility helps you do what you need to do to get a helmet that gives you +38 agility, or +54 agility, or whatever. It’s essentially the same: a periodic, permanent increase in player character ability as a reward for completed tasks.

World of Warcraft was not the first game, nor will it be the last, to utilize acceleration flow. Indeed, some of the development of acceleration flow done by WoW has undermined it. Moreover, there are many different ways that game designers of other games have employed acceleration flow in their games. The rest of this article describes:

(1) The psychological causes and subjective experience of acceleration flow

(2) The methods and insights that players use to achieve a state of acceleration flow

PART 2: Next Week’s Update

(3) Ways in which designers can cause, shape, extend and restrict acceleration

(4) Experimental design to test the various facets of the acceleration flow hypothesis

Obviously, this article is intended to be useful in explaining elements of level-up game design. But because it deals with isolating how, when and why an idiosyncratic flow state occurs, it can also be useful for players who want to try these often-exhilarating techniques in the games they play. Finally, acceleration flow is not limited to RPGs; not even close. Katamari Damacy is one of the best examples of acceleration flow there is. How it does this without being anything like an RPG is described below.

What is Accleration Flow? Causes, Effects, and Player Subjectivity.

Leveling up is always relative. In Baldur’s Gate, gaining one level is a fairly long process, and having a score of 20 in the intellect stat is remarkable. In Disgaea a player can gain ten levels by accident, and having a score of 20,000 in the intellect stat is relatively low. American single-player RPGs tend to favor lower level caps, while Japanese single-player RPGs frequently adhere to the 1-99 model. MMOs are more complicated in that everything they make a player do is part of a latent level-up system, and their level caps are constantly changing.

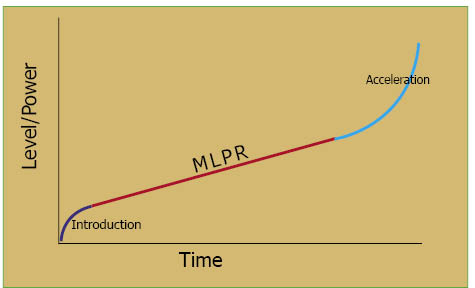

But every game with a level-up system has a rhythm. A good level-up system will tell the player what the "normal" pace for leveling up is. This pace will generally emerge by the end of the first quarter of the game, although it can vary if the game is divided into sections, difficulty settings, or expansion packs. Generally the pace of RPG will resemble the graph below. (This is a simplification; for examples of more specific structures, see part two of this essay.)

At first, in the introduction period the player character will gain levels fairly quickly. The purpose of this is to introduce the player to how the level-up system works, as understanding it is an essential part of the game. Most games, regardless of genre, will have everything happen quickly in the beginning: quests, levels, etc. After the introductory period is over, the pace will assume its most common speed. This common speed is what I refer to as the median level progression rate (MLPR). This is the baseline rate of the level-up system against which players will measure their progress at any given time.

The MLPR can vary greatly from game to game. In something like Final Fantasy 7, the MLPR could be about one level per hour. In an MMORPG or an online game like WoW or Call of Duty, the MLPR might be one level per day. All that matters is that there is a clear MLPR; only then can designers create a space in which acceleration flow is possible. The player gets used to the MLPR, and learns to be able to predict how often they should be leveling up to succeed in the game.

Now, when I talk about the prediction horizon for a game with level-up elements, I mean something different from the usual definition. Normally, the player prediction horizon refers to how the player can predict which gameplay skills will be useful, and which gameplay skills aren't worth developing anymore. Players can’t always guess which skills they need to develop, so the designers need to to teach--and sometimes refresh--those skills before they test them too harshly. Moreover, they need to teach players how fast they ought to be cultivating those skills for future attempts. This is part of the foundation of videogame design.

The prediction horizon for a level-up system is different, and has two parts. In a level-up system, many or most of the relevant skills are not learned by the player, but rather by the character; there aren't too many timing issues or button combinations to master. Sometimes these hand-eye coordination skills coexist with a deep level-up system, but it’s not often that they are completely integrated. Accordingly, the prediction horizon is based on two essential questions.

(1) How fast is my character/characters gaining levels, gear, etc? (2) How appropriate is my level-up rate to the MLPR? (With the possibility of being lower, just right, or higher--which is the case during an acceleration.)A player's sense of the MLPR will make the "lower" and "just right" options clear. The possiblities for being higher than the MLPR, however, could rise seemingly to infinity. (Again, this is a subjective trick.) Because the player has been conditioned to think that leveling up is a good thing, this somewhat mysterious limit above the MLPR is exciting. The player doesn’t fully understand how powerful their character is going to end up when the acceleration is over. In fact, in some games, the player may infer a coming singularity state where the characters become infinitely, game-breakingly powerful. This is an impossible outcome, but it’s the result of a psychological trick imposed by a limited prediction horizon; and it feels great.

The Subjective Experience of Acceleration Flow

The subjectivity of a player experiencing acceleration euphoria can be illustrated by an analogy. Imagine that you are sitting down to a five-course meal. This never happens, anymore, but it’s not hard to imagine. The first course is good. The host tells you that the second course will be better, and it is better. The host then announces that the next course will be even better than the last. And he’s right again! Not only was the third course better than the second, but the jump in quality between the second and third courses was greater than the jump in quality between first and second. The meals are getting better by increasing degrees. And then this happens again with the fourth course. It was way better than the third course!

So now you’re waiting for the final course; the host says that it will be the best course by far. Naturally, you’re incredibly excited. Not only was each course better than the last, but the jump in quality was progressively more than the previous interval. The natural expectation is that the fifth course is going to be ridiculously good--just off the charts. It takes a very resolute cynic not to feel this way; this is what the human brain does: it infers patterns. As you wait for that final course, you are fidgeting in your seat, and you are very excited.

That excitement is the same feeling a player gets during acceleration flow. The fulfillment of that excitement will actually end the effect--end the flow. For example, the final course itself could come out two ways if true. (1) Your host promised it would be the best course, and it was. But it was only a little bit better than the fourth course. You’re disappointed, at some level. The final course is great, but it’s not as great as you were expecting. Still, it’s a very nice meal; to complain would be wrong. (2) The final course is better by far than any other in the meal. The leap in quality between course four and course five leaves all the other intervals in the dust. This might be the best thing you’ve ever tasted. Still, though, your excited anticipation has disappeared. While the anticipation might have made the meal better, it has been replaced by satisfaction, which is a totally different feeling. Satisfaction is about what is taking place in the present, not what might happen in the future, and can exist without any excitement at all.

Obviously I’m dramatizing all this to make a point. The analogy isn't perfect. For one thing, no meal will keep you literally full forever, whereas leveling up is a permanent condition. Permanence adds a lot of psychological value. Moreover, the metaphor isn't perfect because a level-up acceleration is a continuous process not mimicked exactly by too many real-world things. Regardless, plenty of people have experienced an anticipation (call it over-hype if you will) that belies the quality of the thing anticipated. The stakes of a videogame are low, relative to ordinary human affairs. No matter how good a level-up system is, it’s not going to solve day-to-day human problems, except maybe boredom. Nevertheless, the psychological trick of power increasing exponentially beyond the prediction horizon--power that is permanent--is still able to elicit fairly intense involvement from players.

MLPR Metrics, The Living Trophy Effect and Economy of Effort

Like any intense high, acceleration flow can let a player down in a big way when it ends. To combat this kind of disappointment, it's important to understand what the player is doing and feeling during acceleration, from a quantitative point of view. Metrics play a big role in this quantitative analysis. For example, when assessing the degree of an acceleration, the appropriate metric is the acceleration's peak degree of deviation from the MLPR. (It’s probably best to use a percentage to measure it, especially when studying across different games.) This metric explains the designer’s relationship to the acceleration in a few ways, and lets them plan for the end of the acceleration. Peak degree of deviation from the MLPR reveals:

(1) Intention - A large peak deviation can indicate that a designer intended for an acceleration. Intention is usually highlighted by obvious late-game level-up methods, like EXP doublers, massive hoards of gear dealt out in one discrete disbursement, an incredibly powerful but easily obtained weapon or ability, etc. An intentionally large peak deviation will usually lead to an enormous challenge, like an exceptionally difficult optional dungeon and/or optional boss.

(2) Brokenness - A large peak can also be an indication that players have figured out a fairly easy way to break the game wide open. This will be obvious when the peak deviation both [a] arrives earlier than the end of the game and [b] decays into a rate lower than the MLPR for significant portion of the subsequent gameplay. I call this decay an experience correction; it generally takes the player back to the MLPR after plunging below it for a significant period of time, once the acceleration has worn off.

(3) Sectionality - A small-to-moderate peak deviation can be an indication of the end of a section of a game. This usually happens at the midpoint of a game with a level-up system, acting as a kind of “first climax” that allows initiates the player into the more difficult second half. This is a fairly common structure in games, and is discussed later in the third section.

Brokenness, especially the experience correction, can be a letdown after the thrill of acceleration. Following any acceleration will be the period of god-like ease. Especially in very hard games, this period is very entertaining, and in a sense it emulates the traditional feeling of flow, where a player is able to take on the hardest challenges without experiencing too much stress. Still, it won’t be long from the point the game gets easy that the player will become bored.

There are ways to deal with this, however. This god-like power could fade into the living trophy effect, wherein a player completes an acceleration and shows the results of their accelerated leveling (their ascended character, the ‘living trophy’) off to other players. This is most common in multiplayer games, naturally, but it often happens during the early days of a single player release among friends. However players manage to share their accomplishment, the living trophy gets its power from the limited prediction horizon. Players who haven’t performed the acceleration cannot quite comprehend how powerful the characters are who have been through the process; post-acceleration power seems impossible. This creates a sense of inflated accomplishment, which is reasonable compensation for the loss of the acceleration itself. Indeed, some players who are dulled to the effects of an acceleration thrive only on this trophy effect.

Add to the living trophy effect its economy of effort corollary. If two players both reach maximum level in a single or multiplayer game, but one of them reaches it significantly faster than the other because of acceleration techniques, they have another thing to brag about: the economy of effort. Acceleration is great for its own sake, but it also can make showy RPG players maintain that “unbelievable” aspect even among players who have characters of equal power.

Or... Just Finish the Game

It is also possible to mask the effects of acceleration withdrawal by ending the challenge or game completely. This seems like a no-brainer to say, but it’s a legitimate technique when used well. There are two ways to do this. First, let the acceleration begin and end just before the end of the game. When the acceleration ends, the resultant boredom will cause the player to seek the last challenges. The process of acceleration must either involve or trivialize all the remaining challenges. The excitement of doing all there is to do and/or finishing the game will bring the player down from their acceleration gently. The second method is more artful and more difficult. The designer must construct the conditions for the acceleration so that they encourage the player to reach the peak of the acceleration at the last challenge. This will result in a spectacular climax, the artistic effect of which will endure beyond the end of the game.

Delta Deviation: Predicting the Flow

Degree of deviation from the MLPR provides a lot of important information, but it does not reveal when acceleration flow is going to occur. One of the most important factors in predicting acceleration flow is knowing how the acceleration moves the prediction horizon closer to the present. The player, by definition, can’t make particularly accurate assumptions about what lies beyond their prediction horizon. Consequently the closer the prediction horizon is to the MLPR, the greater the subjective feeling of acceleration for the player. To measure the proximity of the prediction horizon to the present, use the rate of change (derivative) of the deviation from the MLPR. An increasing rate of change causes the player prediction horizon to move asymptotically closer to the present.

Like everything else in level-up systems, this movement of the prediction horizon toward the present is relative. The prediction horizon for every game is as different as the respective MLPRs for those games. The derivative of the MLPR deviation should reliably correlate to the experience of acceleration flow, however. A study of how close various games come to the prediction horizon to cause acceleration flow would be a fascinating one that would really lay out a usable framework for developers to pick from. Unfortunately I don’t have those kinds of resources at my disposal. If you think you might, make sure to see the Experimental Design section at the end.

The R/C and R/T Ratios

Experience points are arbitrary. Is 2000 EXP a lot, or is it barely anything? Assuming they're paying attention to them at all, players don't really want to know how many points their characters are earning. Players want to know how soon the next level-up, piece of gear, or new ability will come. To figure this out, players simply estimate what percent of their next level these experience points are. This is not to say players are playing with calculators and paper, but after a few battles or quests, most players will get a good idea how far away their next level-up is. As I mentioned before, this is the first part of a level-up system's prediction horizon.

The second part of the prediction horizon, the MLPR, tells the player whether or not this percent-of-a-level reward is fast and easy enough. So when a player is thinking about leveling up, they're really thinking about two ratios that are operating beneath its surface. These ratios (closely related) are Reward / Challenge (R/C) and Reward / Time (R/T).

Naturally the "Reward" is the percent of a level, or percent of the cost of an item, or percent of a new ability learned, etc. When studying this ratio, just use that percentage.In the R/C ratio, rating "challenge" is a little bit trickier, since such a rating system relies on player opinion. The player's opinion is the only thing that matters, when it comes to an acceleration, however. It doesn't matter if the player rates the challenge as a 10 out of 10 or a 5 out of 10. What's important is that the player will become aware of a possible acceleration when the challenge goes down more than the reward (percent of a level gained) does.

For example, a player is fighting encounters or doing quests in an area, and s/he gets some new items, or learns some new skills, or even just discovers a new tactic. (Specific methods for reducing C or increasing R are discussed below). Because of this, the challenge level plummets. The reward, however, is close to the same percent of a level-up amount it ever was. The player is still earning a healthy amount of experience, money, and/or usable items and it’s easy. In fact, the quests, enemies, and tasks are actually getting easier as they feed the player’s stats, abilities, and equipment. So the player sticks around and continues to play in the area where this is happening. And why not? He or she is getting quite powerful, and it’s not only easy, it’s getting easier faster than the reward is diminishing.

(The same is true for faction points, ability points, gold, boss-kill badges, what have you. It's all the same thing.)

The feedback loop kicks in, and the player character starts to gain levels/gear/abilities with increasing ease. The player is delighted by this, because the rewards from the battles, quests, or tasks tell them that they are completing tasks which are intentionally hard (based on the reward) with ease. Moreover, those tasks are getting easier faster than the reward is getting smaller, so the acceleration extends some distance beyond the prediction horizon. The player experiences acceleration flow, and it all happens because of how the player perceives the growth of the R/C ratio and chooses to exploit it.

Embezzling

One strategy that takes advantage of a modified R/C is what I call embezzling. There are a few forms to this, but they all involve concentrating every level-up resource into one character, ability, or strategy. In Final Fantasy 6, for example, the experience points gained are an absolute amount designed to be distributed among 4 party members. It is possible to let three out of four characters in a party die or get turned to stone just before the battle ends. The experience for all four will get concentrated into one character, whose level will soar quite quickly. Leading off every single battle with a the same Pokemon (in the series' earlier games) to concentrate EXP is another method.

The character (or ability, item, summon, etc) that benefits from embezzling will grow markedly in power. Although the total number of experience gained would not normally be enough to make the party significantly stronger, when concentrated into one character the player cannot help but feel that s/he has managed an acceleration, with all the positive feelings that can accompany it.

Riding

A similar method for manipulating the R/C ratio to achieve acceleration is a strategy I call riding. This strategy involves a distant player prediction horizon; it’s usually employed the second time through a game. The player “rides” an ability or character for as long as possible so as to save up fungible resources for a later, much stronger and acceleration-prone tactic. For example, in Diablo 2, rather than invest talent points into the “Blizzard” spell, a level 24+ sorceress uses it in un-upgraded form, or relies on older abilities. The player saves those investment points until level 30, at which point the powerful “Frozen Orb” and “Cold Mastery” abilities become available. Because of the stored-up points, the player is able to invest in both these new abilities every level, instead of having to choose one. These fungible talent points become a means to acceleration.

This can happen in many games. In Pokemon, because of the hidden Effort Value counter, it is wise to not employ your best monsters until the player has free rein of the map to poach the right enemies for growth. Similarly, in Final Fantasy 8, it is wise to keep the characters with the best limit break (super moves) out of battle as much as possible. The player “rides” the weaker characters through most of the game. Later in the game the best characters can be equipped with a number of stat-boosting abilities that make the value of each level-up worth more. In general, this strategy allows the player to specifically calibrate the level-up process so as to perform an acceleration.

Exploiting the R/T Ratio

The other ratio of importance is reward / time; this ratio correlates with reward/challenge but is different in a few respects. When the challenge of a task decreases, the total time spent on that task also usually decreases; it takes less time to perform a simpler task. When the reward in the R/T stays the same or increases, however, the player feels the fullest extent of acceleration flow, because the prediction horizon is measured in time, i.e. “How long into the future can I predict the growth of my character’s power?” One typical way to do this is to drive up the reward using skills and equipment that increase EXP, provide extra loot, bring in faction points, etc; there are dozens of examples of that. A less typical example is the experience and stat-point perks from Fallout 3 (“Educated” & “Comprehension” plus bonuses in the intellect stat); the player not only levels up faster, but each level is worth more, increasing the effect.

Driving down the R/C will often yield a more favorable R/T as well, but this is not mandatory. It is possible to drive down T without directly affecting challenge. I call this strategy liquidating, although I’m not in love with the term. In this situation, the player is confronted with a difficult enemy that yields high rewards. So the player throws money at the problem, so to speak. Most games have a number of non- (or slowly) regenerating resources like mana, ammo, consumable items, stamina, etc. When consumed rapidly, these resources can shorten the battle, quest, etc, driving down the time factor while leaving the reward the same. This leads to the positive feedback loop as, generally, these resource pools grow as the player levels up. And thus, acceleration flow.

This might seem like it affects the challenge factor, but because it’s not a permanent increase (a level up) it’s really not so. Liquidation is the reason why bosses, who are clearly stronger than normal enemies, can seem easier sometimes. The player is willing to throw resources at the boss because there is only one, or only a few. Indeed, the player is willing to throw resources at the boss because s/he knows that the boss is harder! The challenge level presented by the enemy isn’t really changed; the way the player plays the game is different. Basically, the player is spending consumable resources instead of time. Usually liquidation will take place near an inn, save point, shop, or mission hub that can restore the non-regenerating resources periodically. To stray too far from that restoration point would endanger anyone practicing liquidation, returning the game to normal difficulty and speed.