Robo Explains it All

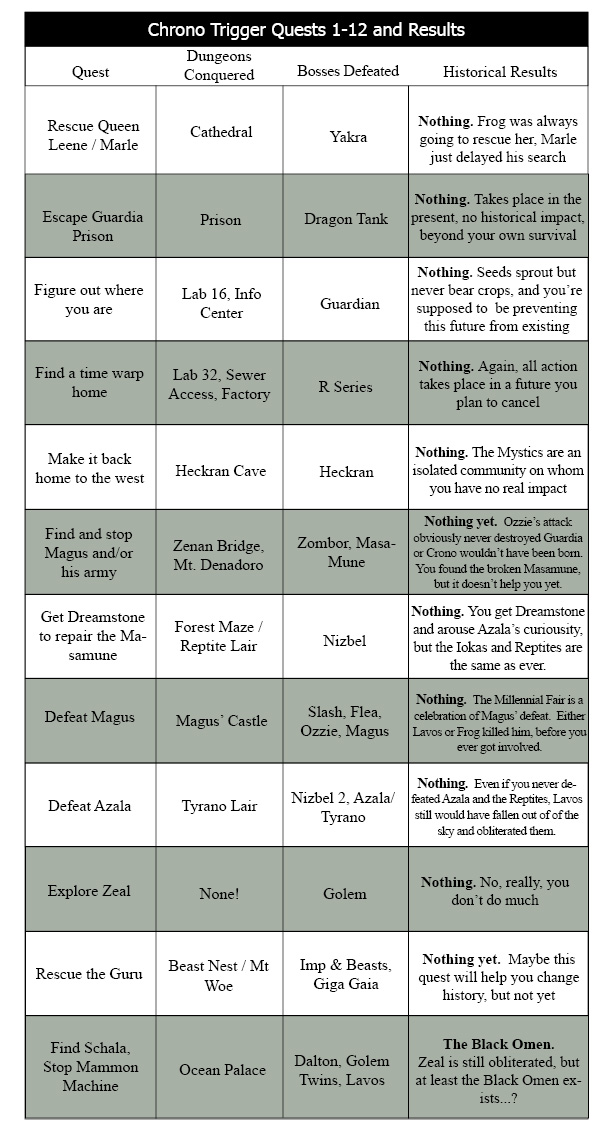

Before we get to quest 13, the denouement of the tragedy, we’re going to take a look back at the first 12 quests to show you how Chrono Trigger has been deceiving the player this entire time. Take a look at the chart below.

This is probably at odds with what the player feels. The player feels like he or she defeated Magus, that defeated Azala, brought hope to the future, rescued Queen Leene, and so on. The truth is that all of those things are historically insignificant. The Millennial Fair is an event that commemorates the defeat of Magus.

Presumably, Magus died while summoning Lavos, since his encounter with him at the Ocean Palace ends in defeat as well. The Reptites were wiped out by Lavos and the ice age that followed his arrival. The future remains as bleak as ever, despite the party’s actions, because Lavos still reigns over the wasteland. There’s an ongoing theme here: Lavos is at the center of everything, and all attempts to change history are disrupted by his presence.

The point of the Tragedy of the Entity is to make the party (and the player, through the gameplay) understand the Entity’s grief. The Entity and its fellow beings have been the victim of Lavos time and again. Lavos has destroyed civilizations and species, warped the planet to its own ends, and then sucked the life out of it. (The general consensus among fans of the game is that the Entity is a kind of animist incarnation of the planet—a kind of nature god.) The tragedy that culminates in the death of Crono is supposed to mirror the experience of the Entity for the player. Robo points this out in the second part of the game.

One of the most brilliant aspects of Chrono Trigger’s design is that it forces the player to experience the same frustration in real life that the Entity experiences in the fictional world of the game. The player’s party cannot defeat Lavos, just as the planet cannot defeat Lavos. The player loses the main (and most powerful) character, just as the planet has lost civilizations and even whole species because of Lavos. And nowhere does the gameplay communicate this theme more clearly than in quest thirteen, the final moments of the Tragedy.

Quest 13: How it Feels to be Powerless

Stat of the Quest:Was Crono the player’s best character? Well, it depends what you mean by that. Crono is useful in battles that require both physical and magical damage, which is rare. After you get his best weapon, he deals the highest average attack damage, at least until Ayla hits level 95. If we look at dual techs, the picture becomes even more complicated. From levels 20–60, dual techs that don’t include Crono tend to be about 13% more powerful than those that do. On the other hand, Crono’s dual techs are more efficient; on average from levels 20–60 they deal about 18% more damage per point of MP spent.[13] Thanks to the way that damage formulas work, this damage/efficiency gap widens as the party grows in level. This, I think, is a product of Crono having so many early, low-level dual techs with so many characters—techs essential to the player’s survival in the early game.

Quest thirteen is easily the most annoying quest in the game, but this is entirely by design. The point of quest thirteen is to act as the denouement to the tragedy that peaked in quest twelve. Quest thirteen adds insult to injury. Not only has the player just lost the best character, the foundation of all their best dual and triple techs, but now the game has taken away all the party’s gear and items too! Moreover, the party composition is locked, and as it happened suddenly, the party might be made up of some characters who haven’t learned many techs. This is yet another example of the design of the game cohering to the plot and themes. A moment of despair and frustration for the characters is mirrored in the frustrating gameplay.

To compound the player’s frustration, quest thirteen takes place in a frustrating dungeon. Properly speaking, the Blackbird is not a maze, because it’s laid out on a grid. Once the player can visualize the way the air ducts and cells overlap, it’s not hard to navigate. There’s only one instance where the player cannot access a room with an item chest in it from the main floor. That said, the dungeon is still frustrating because the player has to climb up and down between the two levels and must avoid combat for lack of equipment and items. Ayla can fight even without her gear, but if she’s using techs, she’s got nothing to replenish her MP with (and the same is true for whoever is healing). The Basher and Byte enemies are, fortunately, pathetic; they have HP and damage more suited to Denadoro or the Reptite Lair. But if Ayla wasn’t in the main party and hasn’t learned a lot of useful techs, it can be a nerve-wracking first trip through the dungeon for a first-time player, as the HP of the party is slowly whittled away, with nothing to restore it.

The Blackbird isn’t meant to be deadly; it’s just meant to feel deadly because the player has lost Crono and all their gear. It’s just the last artful deception in a game full of them. The Golem Boss is yet another part of this attempt to disconcert the player. The Golem Boss counts down as though he were about to unleash a massive attack, the way the Black Tyrano did in quest nine. Naturally, first time players will go all out to try to kill him in a rush. The countdown is a red herring, however; there is no attack at the end of the countdown. The boss seems like it might be dangerous, but it’s just a trick to make the player nervous.

PART TWO: THE COMEDY OF THE SAGES

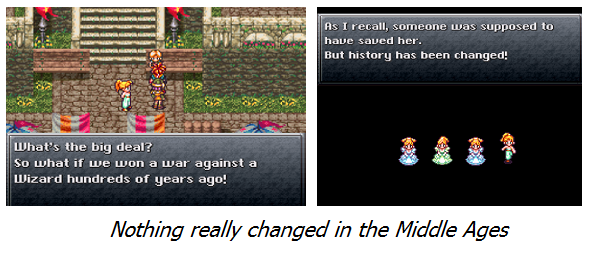

One thing the player ought to have noticed while playing through the Tragedy of the Entity is that Chrono Trigger has been extremely linear. For a game ostensibly about time travel, this is curious. Even while in possession of a time machine, the player has been mostly unable to control where or when the party was headed. Whenever and wherever the party went, their historical impact was basically nothing. Indeed, not only was the quest linear in the first part of Chrono Trigger, but the world in which those quests took place was basically static. When the player finished a quest, there were very few signs of change, except for that some NPCs would react with a kind of “Way to go!” phrase, if they were local to the events of the quest. This changes completely in the Comedy of the Sages. In the second half of the game, the player gains freedom, agency, variety in quest structures, and a much different ending.

To some degree, this style of second-half gameplay is built out of JRPG orthodoxy and Chrono Trigger’s adherence to it, but there are a couple of reasons why the mold doesn’t fit exactly. The key aspect of Chrono Trigger that separates it from typical JPRGs is that the difference between halves is much more marked than other JRPGs. It is a common structure in JRPGs for the end of the game to be more open, non-linear, varied, etc., than the beginning. Most of the Final Fantasy titles operate like this. The player must master the systems the game teaches before being let loose to tackle the most difficult content. Chrono Trigger does fit this trend, and it’s arguable that the second part of the game is merely the non-linear ending that many JRPGs of the 90s offered, but again those differences arise. First of all, most JRPGs of the time (but especially Squaresoft titles) offered freedom earlier in the game. Final Fantasy games often see the player acquire an airship or other vehicle before the halfway point. That is, the player gets to practice some non-linear gameplay before it’s the only option. In Chrono Trigger, there’s only one small detour (the Dactyl Nest/Hunting Grounds) that’s practical to do out of sequence. When the game finally does open up, the non-linearity, it affords is more profound than in any other JRPG of the time. The player gains access to many quests that have no dungeon, is able to use time travel as a puzzle mechanic and gains the ability to cause changes in the game world far more profound than in other games. We’ll get into specific examples of these things in the quests to come.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions. In fact, the print version of this book has been significantly expanded and revised.