The Rule of Three: Examining Plot, Exploration and Combat.

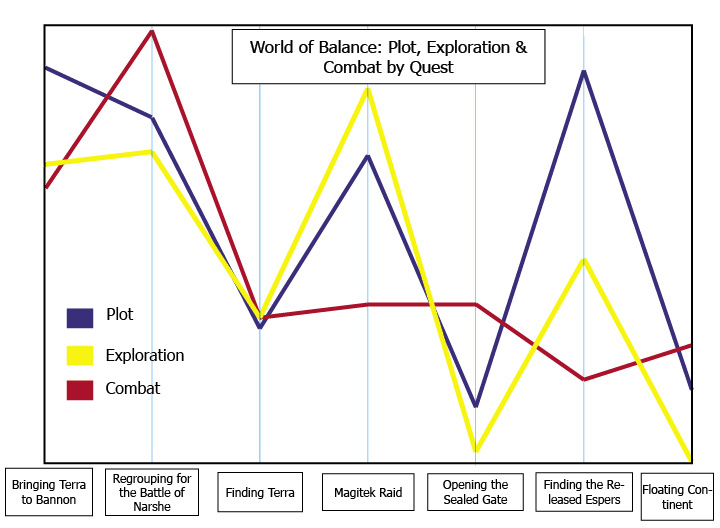

The Short Version The first half of this section attempts to quantify the three constitutent elements of FF6: plot, exploration, and combat, and to weigh them in proportional measure. This measurement is based on the notion that in Final Fantasy 6, like many RPGs, the overall structure of the game is that of linked quests. From the measurement of these elements on a graph, the pacing of the quests becomes very clear, and its pointedness is explained. The second part of this paper analyzes the organizing principle behind the second half of the game: metonymic time. Metonymic time, it is argued, is the emergent factor that provides a sense of fullness, completeness, and order to games rich in simulated skill and non-linear quest lines like FF6. This concept is analogous to the synthesis of skills in action games. The analogous relationship across genres is discussed, and the rational use of metonymic time is suggested with examples.

We'll get to characters (and music!) on the next page, but before we do, there's one last way to analyze how the plot fits in with the game. As I see it, there are three elements to an RPG, and while they frequently overlap, it's fairly easy to spot them. Those three elements are plot, exploration, and combat.

Plot is fairly obvious: it is the story that the game tells to frame the events of the narrative. Some games don't have plots, but most RPGs do. Obviously, it is possible to have many diverging plots in one game; analyzing those plots would be difficult but hardly impossible. When quantifying plot, I counted all the script words spoken on a given quest. As to how I divided quests, I usually looked for a moment in the script where the stated objective changed, you can see my results on the previous page's diagram.

Exploration is all of the non-combat action performed in the world. Exploring towns, viewing optional scenes, talking to NPCs (ironic or not), and many other things are what I term exploration. There is often a lot of overlap between exploration and plot, but not too much in FF6. Moreover, even in games where there is overlap, it is still possible to quantify and analyze the design choices made to create exploration.

Combat seems simple enough; how much fighting is involved in each quest? This turned out to be trickier to tabulate than I expected. How do you assess how much "fighting time" each dungeon represents? There are actually numerous ways to do it, although each of these ways brings up more questions than results. For the purposes of the pacing graph, however, we want to know about is quest design, not dungeon design, because we're still analyzing how the plot, exploration, and combat interact to form our perception of the game's overall experience. (An analysis of the dungeon design, which was often deceptively elaborate, follows on a later page.) So, to analyze how the combat is constructed to form quests, I analyze it using what I call measured time (this is a meaningful term, I promise; see below). FF6 measures time by using a step count; step counts are also used to figure out when to start a random encounter. Dungeons are constructed on an invisible grid, each block of which represents a step for the party. The distance from the entrance of any given dungeon to its exit is a concrete number of steps, given the ideal path. Thus, you can rate a dungeon based on the minimum number of steps that it takes to go through it.

Unfortunately, nobody travels the perfect path through a dungeon, or at the very least they don't do it their first time through a dungeon. There are often distractions, puzzles and the like. Final Fantasy, as a general rule, is not as puzzle-heavy as something like Legend of Zelda or Lufia. In fact, in the WoB, there is only one dungeon with real puzzles--the Cave to the Sealed Gate. Accordingly, when fashioning a combat "score" for each quest, instead of relying upon puzzles to inform me of the accurate length of a dungeon, I rely on treasure chests.

FF6's treasure chests are unusually rich; there are a lot of them and they frequently yield something very useful. (This is especially true in the WoR, but the WoB has its fair share of sweet chest loot.) Players learn quickly to go out of their way to get a chest, knowing that its contents could be extremely useful. What I have noticed is that, because of the usefulness of chests, every chest in a dungeon makes a player more eager to search for the next chest. Accordingly, I gave extra combat weight to dungeons with more chests.

And finally, I added extra points to the combat score for having more bosses in a quest. In any case, the graph is below, and we'll break down its meaning and trends.

Of course, the "scores" on the graph were adjusted mathematically so that they all fit in the same space--that's why there are no numbers. There's no way to make these three elements equivalent, and I don't even try. The point of having them all on the same graph is to show how the designers chose to use each element in what relative proportion for each quest. For example, you can see that the quest to find Terra has relatively less of all three game elements. There aren't too many dungeons, not a huge amount of exploration, nor much plot. This I attribute to pacing. If every quest were longer than the last, the game might feel tedious. The same pacing move happens when the party journeys to the Sealed Gate. The designers are making the middle of the WoB flow by alternating short and long quests. One other important thing to note is how the combat score actually has a downward trend from beginning to end. Exploration and plot jump up and down quite a bit, but the combat score starts high, climbs to its highest point in the second quest, and then descends, plateaus, descends again, and never makes it back to previous levels.

I admit that my scoring system has its flaws, but I don't think that fact alone accounts for what the graph shows. Rather, I think it actually shows that earlier dungeons are designed to be bigger (and slightly more numerous in quantity) but easy. Later dungeons are shorter but much more dense with treasure and difficult encounters. Ultimately this is a design feature that has to do with RDur and DAE, a couple of interesting (if you're an anal weirdo geek like me) statistics that describe exactly what these dungeons are doing. But that's on page seven--we're still talking about story and presentation right now.

Of course those who have played the game (and perhaps some who haven't) will immediately recognize that this kind of 3-pronged analysis can't really be made to work on the second half of the game. While there is plot, it's not linear. Moreover, the gameplay structure of the World of Ruin is flexible as well. The player's ability to choose the structure of the second half means that in order to analyze how the WoR is constructed, we must use a different technique. Thus we come to the ridiculously BLAM-ish, but possibly useful concept of metonymic time.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions. In fact, the print version of this book has been significantly expanded and revised.