In the Loop

Game Loop: An Unconference for Game Developers

by Patrick Holleman

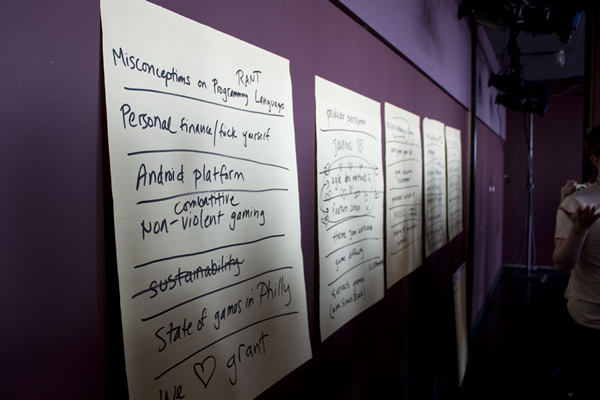

A little after 10:00 in the morning on Saturday May 21st more than eighty gamers, developers, students and journalists stood together in a large room on the sixteenth floor of a high-rise in downtown Philadelphia, and took a vote. The issue they were deciding was, “What do we talk about for the next six hours?”

They had come together for the unconference Game Loop Philly, and as with all unconferences the first order of business is to determine the topics for breakout sessions for the rest of the day. In case you aren’t familiar with unconferences (I’d never heard of them), the name can be a bit specious. There is quite a bit of conferring done in fact; it’s just that there’s no predetermined schedule.

This conference included topics (both official and incidental) such as Brogrammers, procedural narrative, 18th Centry beat-em-ups, Chinese Internet speakeasies, the state of the local game development industry, the role of the producer, how many beers a dev team can drink at lunch, changing business models in games, and Hal Larsson’s first Law of Videogame Difficulty.

(Those are just what I was present for some portion of at one point or another. Even if I’d had a co-correspondent we wouldn’t have been able to attend everything.)

Game Loop started in Boston in 2008, created by friends and colleagues Darius Kazemi (in attendance!) and Scott Macmillan. It’s grown every year since then, and has now spun off its own Philly branch, which, according to the creators, is doing quite well for a first-year unconference. The health of the event was evident in the first half hour when many attendees were already digging into the session topics before the vote had even been cast.

I Want to be a Producer

The first session I attended (I wish I could have been to all of them) dealt with the interactions between game developers and those in the often-misunderstood 'producer' position. I, like many youthful Bullshit Liberal Arts Majors (BLAMs) who were very into gaming in college, entertained the idea of being a videogame producer at one point. This phase came after I realized that "Lead Designer" wasn't an entry-level position. It makes sense, if you start from a position of total, embarassing ignorance. Programmers have to know how to program, artists have to be able to at least draw, musicians must be able to compose. Producers don't have to know any of that stuff, right? They just have to know how to do everything else! Of course, the first assumption is just plain wrong; producers need a strong familiarity with every aspect of production. The second assumption is poorly informed: "everything else" is an awful lot.

Garth DeAngelis, who moderated the panel, structured his session to cut down a lot on the introduction necessary to the role of the producer. I walked in a few minutes late to find the leading question written on the white board behind him. “Producers: Essential Glue or Useless Meatbags?” The overall theme was about what makes a good producer vs. what makes a bad one. This not only clears up what your average producer does, but what an ideal producer ought to do. He enumerated the roles he saw as most essential.

(1) Project manager - This speaks, more or less, for itself and is explained by some other roles. At the end of the day the producer is beholden to the management for getting the project done.

(2) Champion - Someone who acts as a proponent of design ideas or development strategies proposed by a member of their team. If you're a manager, it doesn't matter what business you're in; if your team doesn't think you've got their back, it will be a problem.

As one developer told it, his producer happened to walk by a casual conversation between him and his friend. "We're having a conversation, just us like, 'Wouldn't it be cool if we did this...' and the producer walks by and over hears and says to himself, 'We're doing that!' And then he announces the feature at E3."

That's a trust-breaker right there; don't be that guy.

(3) Communicator - Remember that this is a two-way street: the producer communicates the directives of management and the feedback of other teams to the producer's own team, but also communicates the team's needs and ideas to everyone else. This highlights the producer’s role as the person who needs to have a foundation in all aspects of the production; how else would he/she be able to communicate articulately with anyone involved?

(4) Counsellor - what producer Ryan Harbinson called "the most underrated role." A producer's role is to make sure everyone else can do their job. But sometimes that means more than fixing technical problems or resource shortages; sometimes the producer has to help the team find their motivation and focus again. Sometimes the producer needs to intercede and resolve conflicts. Make no mistake that the human aspect of any production is always at least as complicated as its technical aspects.

(5) Problem-solver - Sometimes the problems that defy categorization are the most important ones. It's the producer's role to tackle these. But in DeAngelis’s mind, it's better to prevent problems than to solve them. "A good producer will do the legwork and planning to prevent those [problems]. When things are going well, you're doing your job silently."

I also learned about brogrammers. They're software engineers who also like sports, fantasy sports, e-sports, Sports Center, sports bars, fist-bumps, clubbing, loafers, pink polo shirts and all the other Freudian underpinnings of an unapologetic male culture. You know. Brogrammers. They write the same code as everyone else, but anyone serving as their producer ought to know that dealing with them is not the same as dealing with a programmer who has more cerebral hobbies. They wouldn’t go into specifics, however.

There was one last little piece of advice that producer Ryan Morrison of Island Officials gave us, one that made that ignorant undergrad inside me feel a little bit better. He said that you have to be passionate about games to be a producer. “If you’re not passionate, you get sensed out.” So, check one box on the list for me, and then throw it in the fireplace.

City of Brotherly Game Development

Philadelphia’s chapter of the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) was the real driving force behind getting so many people to come to the Game Loop. The chapter is surprisingly robust for a city that doesn’t exactly have a national reputation for making games. Back in 2008, I did some research on the game development scene in Philadelphia and didn’t come up with too much, but it wasn’t just me. When the current IGDA chapter leadership took office around that same time, there were four game studios in Philadelphia known to them. Now there are twenty-seven studios and more emerging all the time. The IGDA chapter membership has grown from about fifteen people to more than sixty.

Philly has seen mostly indie and mid-sized development teams, from the mobile platform developers AMI/Megatouch and Flyclops to musicians/programmers Cipher Prime whose surprise hit “Auditorium” catapulted them into the game industry. According to Cipher Prime’s Will Stallwood, they don't even think of themselves as game developers, but rather as a software studio that sometimes makes games. Still, their new game “Pulse” was an iPhone store Game of the Week, and is accumulating many positive reviews.

The five-man outfit Final Form is made up of a number of developers who got their careers started on the West Coast. They came to Philadelphia to make the game they always wanted to make (the historical beat-em-up Jamestown, available on Steam June 8th), on their terms. When asked why they chose Philly, brothers Tim and Mike Ambrogi said, in perfect, comedy-troupe unison: “The sandwiches!” For them, Philly was convenient for a number of reasons, not the least of which was the supportive culture of the indie studios here. There is a disadvantage in working here, however. Mike explained, “We’re preparing to release ‘Jamestown.’ If that fails I have a choice. Do I want to leave Philly to go work at a Valve or an Id, or stay here and make porn games for Merit [games studio].”

It is true that there is no bedrock of AAA presence that brings in and diffuses talent and money into the local games industry. Such a place would also allow experienced developers to take risks because they could go back to work for a studio after they’ve tried their indie experiments. The group discussed the idea of an EA branch or an Ubisoft Philly, but generally the consensus was that this would change the character of the Philly game scene. Studios like that have their benefits, but they might “poach” talent that is currently doing more innovative work.

Current IGDA chapter chair Matt Brenner believes that the game scene in Philly is going to grow organically. “It’s going to come from game releases and it’s going to come from initiatives that we’re going to do.

“We support each other,” he added. “One of the biggest things that we [the IGDA] have changed is that we try to help each other.” He’s absolutely confident that this growth will happen, too. “We’re gonna see success. This is going to be one of the biggest 6-8 months for us.”

There are certainly more games coming out in the city than ever before, and more companies starting new projects, new indie outfits that appear all the time. “Philly is making games,” Brenner said. “Let’s get that message out in Philly.”

No Restaurant for Old Men

Even lunch was interesting. The thing about the games industry, as anyone who has been to GDC will tell you, is that everyone knows everyone else. Or at least that statement is nearly true. So when a local game dev chapter gets together, it might as well be thirty close friends. It was also Saturday afternoon, and I think it was happy hour in Iceland by that point, so hey.

I counted about 5 pitchers of beer at my table alone. Needless to say, opinions were significantly more forthright in the post-lunch sessions. And yet everyone seemed so much friendlier. I was asking a musician attending the Loop if he knew the music of game composer Yasunori Mitsuda. “Actually no I—” he managed.

“YES!” a slightly inebriated programmer three seats down said, entering our chat. As he said this he reached his surprisingly long left arm across the table in a gesture of pointing confirmation. Then he blinked, and went back to whatever conversation he had been a moment before.

To be fair, if someone had said the same thing about Mitsuda in earshot of me at the same time, I might have done the same, except that I was holding my sandwich. (And I was drinking water.)

Death, Taxes, and Retail Markups

A good argument, no matter the subject, is one in which all sides make their case clearly and intelligently and with passion, but nobody gets angry. I had the uncommon pleasure of being present for one of these discussions. The topic was "Changing business models," (in Games, naturally), covering free-to-play, changing retail price points, and most importantly digital distribution. Both gamers and developers attended, which accounts for the heat of the debate, and most people had a good point to make.

The biggest problem, according to session-goers, is that the current retail market makes things difficult for just about everybody. There are too few distributors who are not always directly in competition with each other. And then there's the ubiquitous $60 retail price point. Ryan Harbinson from Island Officials said, "Sometimes day 1 at $40 sells millions, but the publishers are so jammed in that $60 price point." The higher opening price point is for people who are going to buy the game day one no matter what; that's a classic retail model for more products than games. But the price is not the only problem, there's also bullying from retailers like Gamestop and Wal-Mart, who have enough power to be able to dictate price points, sale conditions, margins, etc.

The solution to most of those problems is digital distribution. Services like Steam, Xbox Live, the App Store and Battle.net all avoid the pressures that retailers can put on a publisher by going straight to the customers. This can be great for the big publishers--and that's important because we want them to keep making games. Sometimes it saves the consumers some money too. Those services are only useful for a developer if they have an agreement in place with a publisher. With a good prototype of a game, a publisher will certainly take notice, but even prototypes aren't free to make. And good luck conducting an extensive beta test without the marketing machinery a publisher affords.

To solve the first problem, we talked about Kickstarter. If you haven’t heard about Kickstarter, visit the website. It’s a crowd-patronized system of investment, particularly good at the micro-loan level of funding. The project manager (a game, for our hypothetical example) sets a target budget, and until pledges reach that sum nobody pays anything. Obviously I’m not going to explain it better than they do, and this is the internet, just go. But as long as we’re on the topic, there are a few cool games that have gotten funding through this model. Chief among them, in terms of charm, is Cthulhu Saves the World. I’m sure we’ll have a big hit from this model soon enough.

In some cases, however, it's possible to solve both the funding problem and the beta problem with one master-stroke: the open beta. We all know the success story here: Minecraft, which, to do one better, was an open alpha. Of course Minecraft is a rare phenomenon in many respects. The players have paid for its development, so it still falls within the category of a patronized work—but it gets even better: the Minecraft community worked extensively to help identify and fix bugs in the game, setting up things like Minepedia, which is surprisingly civil for an unofficial forum. But inasmuch as news about Minecraft is not really news, I’ll say “Buy it if you haven’t,” and end there.

As the group pondered a future where games are less and less dependent on retail outlets, a cynical question emerged. Steam has been the target of more than one attack by retailers, most recently when UK shops threatened to ban publishers who used the service. It didn't take; Steam is powerful, and so are the publishers who use it. If a real complication to digital distribution were to arise, it would probably come from those who control the digital channel: internet service providers. Digital distribution isn't just for games, after all; lots of software goes out that way.

As the digital market grows in value, someone is going to want to grab a piece of the margin that retailers once held. It's not ludicrous to think that there might be a "software download" surcharge coming from ISPs in the future for certain major digital outlets. I'm not expert enough to know the legal guidelines surrounding this (if you are, email us from the submissions page), but even if it isn't legal to levy this kind of tax right now, just wait until the digital distribution industry reaches billions of dollars in value. ISP lobbyists will have an easy time persuading lawmakers to allow an ISP surcharge which can then be taxed; even at pennies on the dollar it would be a new stream of revenue for the government. And if you think, 'Hey, ISPs are pretty negligent about torrents, how could they possibly crack down on an entire industry?' I would respond that ISPs have very little to lose from torrents. Torrents are a public relations problem, for the most part. When billions of dollars of revenue are on the line, the ISPs will find a way to secure their income.

This led the discussion to the joke, "So now there's gonna be an Ice-cream man for the internet?" It's a funny idea, a travelling vendor who has their own satellite Internet and can show up to install a program for a nominal fee, but it's not completely absurd. What's more likely, the group decided, were independent Internet kiosks in stores, malls, and cafes. In fact the idea of an independent internet cafe where members can dodge the ISP surcharge seems quite plausible indeed.

Believe it or not, this kind of independent Internet hotspot actually exists in a slightly different form, in Mainland China of all places. The Chinese Government maintains a tight control the legitimate internet channels. For the game industry this means that the government says not only what can sit on Chinese store shelves, but also what can be digitally distributed. Moreover, the government also has controls over how long gamers can play online, in some cases. One of the session attendees--we'll call him "M" since the government could ban his re-entry into the country--told us about Chinese internet speakeasies. There, using what can only be called "black market internet," Chinese gamers are able to play whatever and however they want.

Apparently, they take the security of these internet back-alleys seriously. After playing games at his nearby speakeasy a few times, M found himself locked out, under suspicion of being a spy. Why the Chinese would hire an American to spy on their gamers, I don't know, but you can never be too cautious when World of Warcraft is on the line.

Ultimately, however, this does prove that entrepreneurs will enable digital distribution on their terms when broadband channels are somehow controlled. I think it should come as no surprise if Western publishers mount a similar defense of their distribution rights. Steam was built for the express purpose of letting Valve avoid retail. Is it so crazy to think that Steam subscripions would come with USB modems built for the specific purpose of streaming downloads?

The Computer is a Cheating Bastard

The "Game Difficulty" session did end up devolving into a rant for a while. It was an unusually friendly rant; it didn't stay on one topic for too long. Between Devil May Cry 3, Multiplayer in New Super Mario Bros Wii, and "Super Meat Boy," the group generally decided that there are two kinds of difficulty. The first kind of difficulty is a learnable set of skills, the second kind is random crap. This, in turn, caused Hal Larsson of Final Form to talk about how playtesting their upcoming historical beat-em-up "Jamestown" caused him to think critically about how games can be difficult but fair. The result: Hal Larsson's First Law of Game Difficulty:

The ability of a developer to punish a player with difficulty is inversely proportional to the total respawn time of the player avatar.

(Hal, center, gives us his wisdom.)

Or, in other words, get that player back in the level, back to that challenge as fast as possible, and they'll forget what a giant pain in the ass it is to fail so often. In the words of Larsson: "People want content, but cheap difficulty is not additional content. What I've been doing is hand-touching every piece of content. It feels like new content [at higher difficulty], not like cheap difficulty. The metric that I find useful is 'whose fault will the player think the death was?'" It’s certainly an interesting perspective to think about, whether you’re a game developer or just a gamer who likes to know that their frustration can sometimes be accurately blamed on the designer/computer. Also, on the topic of take-away messages: don’t multi-play New Super Mario Bros. Wii with anyone who sleeps in the same house as you.

All Good Unthings Must Come to an End

How do you close out a meeting that had numerous simultaneous sessions and no plan coming in? You say thanks, and that you want to do it again. And then you start planning for next year, I suppose. To all of you within traveling distance of Philly, the website to keep tabs on it is here. There’s also some links to stories and sessions I didn’t cover. You can also follow the group on twitter @gameloopphilly, or check out the pictures at the Game Loop Philly account on Flickr. And if you want to know more about that 18th Century beat-em-up, or how a music game like Pulse gets made, stay tuned to the Game Design Forum. And, click that button just below.