Finding Complexity in Wide Levels

A large portion of the content in phase four exists outside of the mandatory dungeons. The purpose of this content is to allow the player to build his or her party’s power through means other than repeating the same few battles in the final dungeon over and over again. Earlier I talked about the concept of “wide levels.” In order to explain what this term means, it’s necessary to provide some context to how we think about level-based progression systems in RPGs. Since the days of D&D, a level-up has always been a permanent, periodic increase in character power. The most obvious example of this is when a character goes from being level 23 to level 24. That’s a permanent condition; it happens at regular intervals as measured by experience, and it’s an increase in power. Several other events fit the same criteria, however. An obvious example of this is the levels gained by materia, which go from casting simple spells to more powerful spells, or which allow the player to cast a summon spell multiple times per battle as they grow in level. Equipment is also a form of level-up. The growth from level 23 to level 24 is qualitatively the same as the growth from the Titan Bangle to the Mithril Bangle. Gear may not seem as permanent as character levels because players often sell it—but they only sell their old gear when they have access to a new and better piece of gear. Players can’t “sell” level 23 when they reach 24, but they would if they could. Sold or not, gear is just another level-up system that offers permanent, periodic increases in player power.

If levels can take many different forms, we can assess level-up systems in terms of height and width. The height of a level up system is easy to measure; it’s simply the number of increments between the player’s starting level and the maximum. For FF7, the character level system goes from 4 to 99 (no character starts below level 4), for a height of 96 increments. That’s fairly tall, although many JRPGs have passed it since. There are lots of other heights to measure, though. Cloud has 16 weapons to collect, each one a level-up. Every character has seven limit breaks to learn, each one a level-up. But if we’re looking for width, we’re looking to see how many different systems contribute permanently to character power. My count is five different systems: character levels, limit break levels, materia levels, equipment levels and chocobo levels. It’s not immediately obvious how chocobo levels affect character power, but we’ll get to that later. The important thing to realize is that there are many different systems which strengthen the player’s characters.

There’s more to the design of a wide level-up system than merely having different bars to fill. In order for width to actually work as a design philosophy, the player has to engage in different kinds of activities to fill those bars, or else the player is only grinding. Most of the above systems are based on battles, but not all of them. The best materia and gear are both acquired through various kinds of exploration. Although players certainly can become powerful enough to beat Sephiroth and the optional bosses through mere grinding, it actually takes less time (and fewer repetitions) to pursue non-battle tasks in conjunction with some grinding, rather than grinding until the character level cap.

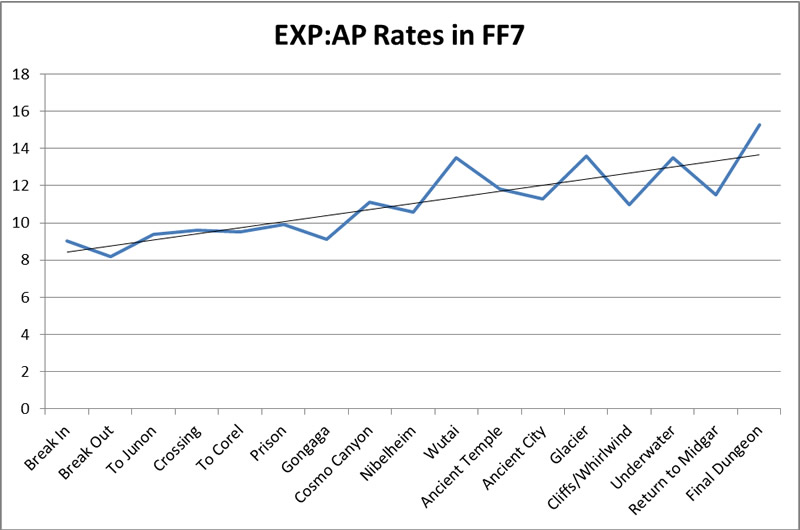

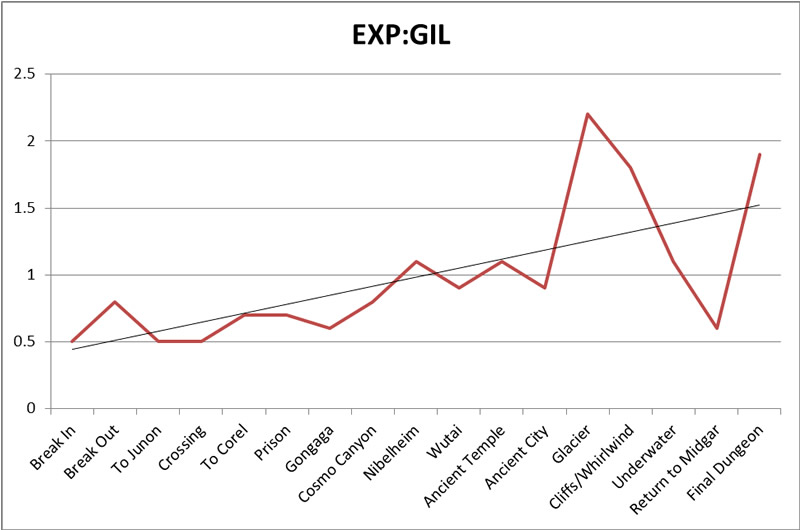

The point of wide levels is to reintroduce complexity that was stripped from battles when character classes disappeared. The really brilliant thing about FF7’s level-up system is not that it’s just wide, but that all of its diverse systems interact with one another in different ways, giving clever players a way of manipulating all of these systems to their party’s advantage. All of the different level-up systems run on different currencies, and these currencies come at different rates. What’s more, those rates change over time. The primary example of this dynamic is the change in the ratio of EXP to both Gil and AP.

[80]

[80]

[81]

[81]

One explanation for this dynamic is that the characters’ EXP needs grow more than their AP needs grow, and the total amount of EXP needed is vastly larger. But this doesn’t explain how the player is supposed to grow materia like Ultima, Contain, Bahamut Zero and Knights of the Round. All of these materia arrive late in the game, start at zero AP growth and have huge AP requirements—without a commensurate increase in AP income. The designers aren’t simply making a mistake here, however; the game is changing to give the player new ways to play the game.

Before players have even thought about the major sidequests, they are met with a puzzle that comes out of the phase four level system. The difference in currency rates has had two important results already: the player has a Gil surplus and an AP deficit. The ratio of gil to EXP has actually gone down, but because the player no longer has to purchase gear, they will start to accumulate it in the endgame phase. An accumulation of money at the end of a JRPG is a fairly common occurrence, and different games have dealt with the surplus differently. Star Ocean: The Second Story features a shop in the middle of its optional dungeon whose contents are so expensive (although they are worth the money) that players can never expect to buy them all. Final Fantasy 8 employed an item transmutation system that allowed players to turn certain common, purchasable items into more powerful items or even directly into magic, thereby putting excess money to use. Final Fantasy 7 takes advantage of the surplus too by allowing the player to invest that money into chocobo breeding. Neither Star Ocean nor FF8 has anything like the AP deficit that exists in FF7, however. (Star Ocean’s ability points system is folded into its level-ups, while FF8’s ability points are actually much easier to farm than EXP is, if the player knows where to do it.) The ideal solution to the surplus/deficit problem would be to turn gil into EXP—and by complicated means, this is actually possible.

EXP Alchemy

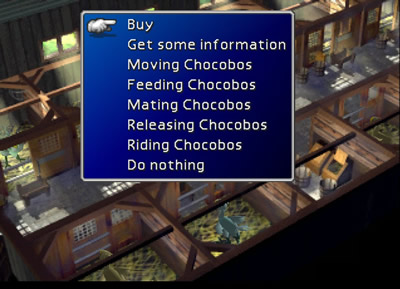

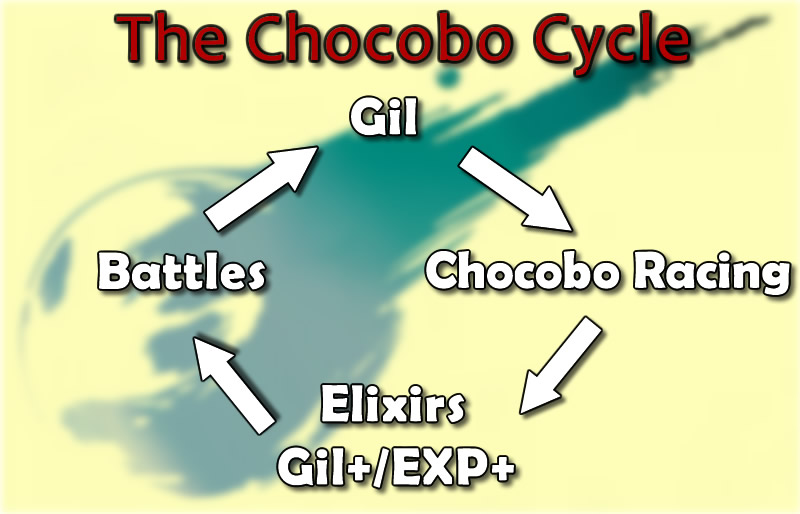

The signature cycle which drives the end-game content in FF7 is the transformation of excess gil into EXP and AP. The means of this transformation is through the Gold Saucer, primarily via chocobo racing. Because the player no longer needs to buy gear, he or she can invest their excess gil into something other than equipment purchases. One strategy would be to simply invest it all in purchasing Ethers, which would allow for the replenishment of MP while in a dungeon. This strategy will work, but it’s not efficient and requires nonstop grinding. Although the upfront costs for chocobo breeding are high and the payoff is not immediately visible, it’s still the best investment in the game.

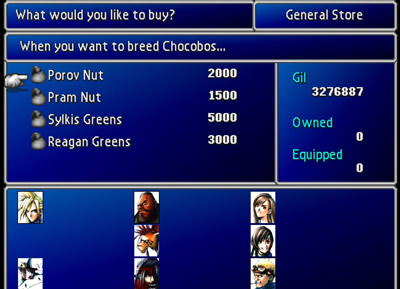

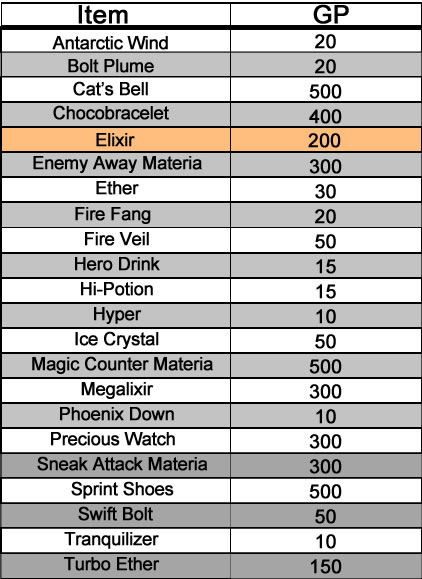

For players who are not duplicating items, the cost of chocobo greens, stalls and nuts can accumulate quickly. The rewards, although not immediate, are extremely good. To the right is a table of items which can be won from races. The items here are a mixed bag. Some of them are useless trash, and some of them are useful but not worth doing races for. Some of them, however, are incredibly valuable. Materia like Enemy Away and Counter Attack have clear uses, but it’s the elixir item which holds the most value. Elixirs can be converted into large amounts of EXP (and decent amounts of AP) through the Magic Pot monster. The Magic Pot can be found in the Northern Crater (its exact position and encounter rate are discussed later.) After being doused with an Elixir, the Magic Pot will become vulnerable and give the player 4000 EXP per hit—or more than ten times the normal per-attack rate. The Magic Pot is also one of the best sources of AP in the game, dishing out 1000 AP, about four to five times the normal rate.

[82]

[82]

Chocobo racing is a great way to earn extra elixirs, since they cannot be bought anywhere. In fact, at the S-Rank level (the highest rank of race) the player is twice as likely to get an Elixir as any other reward. It does seem that the designers made this part of the game with this exact conversion in mind.

One of the great things about the chocobo racing mechanics is that there’s never any wasted effort, because the player never has to accept an item they don’t want. All of those undesirable items can actually be converted into the useful currency, GP, which can be spent at most places in the Gold Saucer—including at a unique shop in the Wonder Square.

The amount of GP scales depending on the quality of the item, but the purpose of this mechanic is to make every victory useful. GP buys one of the best items in the game, the EXP Plus Materia, which will reduce the amount of grinding the player has to do by directly augmenting earned EXP. There are other ways of acquiring GP to buy this item, like the minigames of the Wonder Square. Like chocobo racing, these games require gil, but they take a lot longer to produce GP than chocobo racing. In the end, all of these paths are ways of converting gil into EXP, either through Magic Pots, augmented EXP income, or both.

For exceptionally skilled and/or knowledgeable players, there are other methods for stockpiling Elixirs than chocobo racing. Players who know where to look can use the Morph command to turn several enemies into Elixirs (although this is grinding, which is what they’re probably trying to escape). Players who are preternaturally good at the basketball shooting minigame in the Gold Saucer can rack up GP fairly quickly, too, to buy the EXP Plus Materia. Neither of those things can net the player the unique materia which is strewn about the world map in hidden caves; that is only available through chocobos who can cross terrain which is inaccessible by airship. Those materia are some of the best available in the game, including Mime and Knights of the Round. This is the trick of the chocobo breeding sidequest: it’s always giving the player more than one kind of reward. Racing gives the player three rewards: items, GP and access to higher-level chocobos. Those rewards can be either directly converted into EXP and AP, or else they augment the rates at which EXP and gil come in, giving the player virtually everything they need to face the game’s highest challenges.

The last thing to understand about chocobo breeding is that the way it converts one currency to another is cyclical, and that the cycle accelerates. The starting point of the cycle is a surplus of gil which can be spent in the initial costs (housing) or ongoing costs (feeding) of chocobos.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions.

The Four Phases of FF7 - Back | Next - Enemy Archetypes