Chapter 2: Quests Five through Eight

THE INTERLUDE: THE END OF TIME

The end of time is important--although how it’s important will be explained later in detail. Basically for now we can recognize it as the close of the first “chapter” of the Tragedy, and the break before the beginning of the second chapter. Again, though, we’ll cover more about this establishment of rhythm later.

Quest 5 - The Rational Use of Magic

Stat of the Quest:About one in three non-boss enemies (or “mobs”) in Chrono Trigger is highly resistant to physical attacks. For design reasons, about 75% of those resistant enemies come in the Tragedy of the Entity. For bosses, the reverse of that is true. Of the strictly physically-resistant bosses, 75% of them come in the Comedy of the Sages. The reasons for this division are twofold. First, the early quests have to teach the player when and where to use tech attacks, and also what those (highly varied) tech attacks do. The most obvious way to trigger that behavior in the player is to greatly reduce the damage an enemy receives from normal attacks. Second, enemies in the second half of the game do significantly more damage and have more health (even when taking into account the party’s higher stats), and inflict more debuffs, so making them immune to physical damage would make common battles longer more difficult than the designers wanted them to be. Third, many of the best tech attacks in the game are physically-based and having widespread physical resistance would restrict party composition. Between Final Fantasy VI and Final Fantasy IX, this was not something that the Squaresoft designers liked to do.

Medina village begins another key deception in the game: the red herring on the origin of Lavos. If you’ve been reading the first four quest synopses, you’ll note it’s not the game’s first deception—not by a long shot. Nevertheless, it’s important that the game continually deceives the player in order to keep him or her off balance, and it certainly happens often.

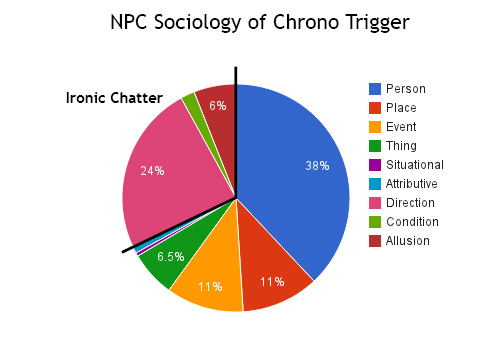

The NPC sociology reflects this clearly. (If you want to know more about NPC sociology, there’s a much deeper description in Reverse Design: Final Fantasy VI.) Typically, NPCs in Chrono Trigger do a very good job of communicating to the player where to go and what to do next. That’s a type of communication called “direction,” by which a game designer gives the player instructions in an “in-universe” way. About 25% of NPCs in the game give the player some kind of instruction about how to play the game. In Medina village, there’s a huge change. Almost none of the residents here give instructions; most give backstory instead. Getting more backstory from NPCs is not unusual, but the concentration on a single topic (Magus and Lavos) is unique in the game. The mystics seem to have spent the past 400 years dwelling on a single unfulfilled event—even though they greatly misunderstand what was supposed to occur. The player is supposed to infer that Magus, who allegedly created Lavos, is going to be the main antagonist of the game. The payoff for this deception won’t come for three more quests, but the setup is in full force already.

The Heckran Cave dungeon serves as a lesson in how to use the magic the player has just acquired at the End of Time. The entire dungeon is filled with tech-only, and, specifically, magic-only, monsters. Fire Whirl will work just fine because it’s still technically magical, but most of the enemies are placed widely to make this impractical. The lesson about using area-of-effect attacks is over; now it’s time to learn how to use—and more importantly how to ration—single-target tech attacks. To that end, most enemies will fall quickly to magic. Marle and Lucca’s first-level elemental spells have damage floors around 120, which will instantly kill any enemy in the cave. If Crono hasn’t reached level 12 or isn’t using the Red Katana, his damage floor might start in the 80 damage range,[5] which would mean he can’t kill the Cave Bat or Jinn Bottle enemies.[6] Properly leveled and equipped, however, all party members should never have to cast more than once per enemy. Additionally, Robo’s Laser Spin has a damage floor around 88, which would end many battles all at once.

The Heckran is much like the other monsters in the cavern, weak only against magical attacks. The Heckran also brings back the design features of the Guardian: periodic phases and severe counterattacks. The Heckran enters a short, periodic counterattack phase (“Go ahead and attack, I dare ya!”). Trying to heal through these counterattacks wastes MP, which the party needs to conserve to cast offensive spells. In the end, it’s simpler to wait for the counterattack phase to end. Interestingly, this is the only point in the game where the player will really wait and do nothing in a battle. After the battle, the Heckran feeds the player a Lavos-flavored red herring, and the party has their next quest.

Quest 6 - A Mountain of Things to Do

Stat of the Quest: NPC Sociology Breakdown!

NPC speech breaks down into several categories, and statistical surveys of those categories can tell us a lot about how the game is designed. Note that the survey below counts the first dialogue spoken by NPCs, or the first new dialogue they say during a new quest. There are very few reaction dialogues graphed, because almost all of the reaction dialogue in the game happens after you complete a quest. Most NPCs local to that quest will give you a reaction dialogue right after the quest but will lose that dialogue when the next quest in their area/era starts.

Quest six is the biggest quest so far and marks the beginning of the only time in the first game where there is a specific, larger meta-quest other than “stop Lavos.” That quest is to find and defeat Magus so that Lavos is conveniently edited out of history. There is a macguffin involved—the Masamune—and this “chapter” will take three more quests to complete. The whole thing is another attempt to deceive the player with various forms of pacing. In this case, the designers were confronted with a problem: how do we make the game feel like it’s ramping up towards a (false) climax without just throwing over-long dungeons at the player? It’s too early for really long dungeons, and Chrono Trigger is too carefully crafted for a sharp spike in difficulty. The first solution to all this was to ramp up exploration activities. Thus, there’s an uptick in non-combat quests, talking to NPCs to find treasures and quest locations, searching shops for gear, trying to track people down, etc. The second solution was to create a dungeon that feels longer and more challenging (at first glance) than it really is.

The exploration activities start the player with a mini-quest, to bring supplies and reinforce Zenan Bridge and finish with a two-town manhunt for Frog and Tata. Having probably never been there, the player has to figure out that the action is happening at Zenan Bridge, then has to talk to numerous people at the bridge and in the castle to figure out that it’s the Chef who is the object of your current task. It’s hardly spelled out. There’s a boss in the middle of all of this; he’s not terribly interesting from a design point of view. Half of Zombor absorbs fire and the other half water. Elemental absorption is, strangely, one of the few defensive mechanics in the game that sees very little development. (Almost all significant instances of elemental resistance are in boss fights, and there are still not that many.) After the fight the player gets even more exploration. Instead of having one new village to explore per dungeon (as has been the norm) there are two. Dorino village offers some items, an allusion to a future sidequest, and a tip to defeat the upcoming boss. That’s all exactly the kind of exploration that RPG players tend to love. The only problem is that the NPCs, for whatever reason, do a bad job of making it clear what the player should be doing. You can count the major flaws in Chrono Trigger on two hands, but the directions to the player in this quest are one of them. Two NPCs in Dorino will inform the player of the Masamune’s supposed location “nearby,” and that the “hero” Tata is after it. All of the relevant NPCs in Porre will speak about Tata, but only a couple say anything about his location.

Denadoro is the biggest dungeon so far (although its size is quite deceptive) and, for Chrono Trigger, it is unusual. Dungeons should get bigger and more challenging as the game goes on; no player will be surprised about that. What is unusual about the dungeon is its structure. So far, the big dungeons have been divided into two distinct parts. The Cathedral had a save point in the middle. Guardia Prison did not, but it was small (if confusing). Lab 16 and the Info Center had a world map segment and a save point in the middle, which was a little odd but still divided the dungeon into two neat parts. The Factory Ruins had an obvious division between the left and right elevators, with a save point in the second section. The Heckran Cave was short enough that, like Guardia Prison, it didn’t need division. Mount Denadoro is a long dungeon, but the only save point within is located one fight before the boss. This is no accident; like everything else in the game it is the designers’ way of playing with pacing. In truth, Denadoro has fewer monsters and fewer total enemies than the Cathedral. It feels a lot longer though, and almost certainly takes longer. Part of that feeling of length comes from that lack of a dividing save point. The player has to do the dungeon all in one attempt. Another part of the length is the battles with Ogans, an enemy with a new design feature: triggered vulnerability.

Want to read more? The rest of this section can be found in the print and eBook versions. In fact, the print version of this book has been significantly expanded and revised.