First Impressions: GemCraft Labyrinth

GemCraft Labyrinth Game in a Bottle Studios / Armor Games, 2010.

Tower defense is a genre that has benefitted considerably from the boom of online arcade and casual games. It makes sense, from a design standpoint: tower defense is quite simple to play, with a lot of potential depth. It's not a genre that requires quick reflexes, or pinpoint accuracy. Most tower defense games are plainly visual, so as to make learning easy. Controls are simple, and it's easy to include a lot of instruction in the UI. Because of all these things, tower defense games are becoming very common; clones are inevitable.

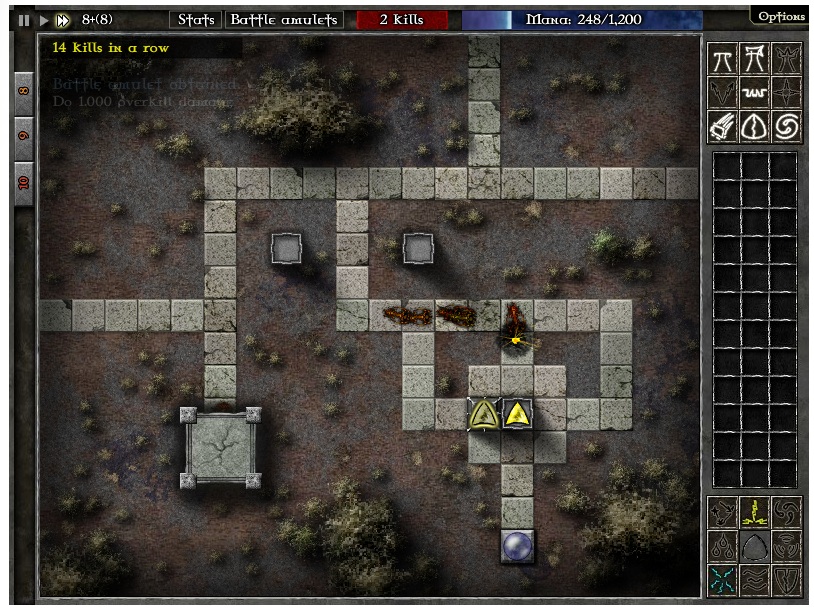

GemCraft Labyrinth takes this accessible genre, marries it to a level-up system, and builds a long and reasonable learning curve. It's also got a playing field that's about as intuitive as any I have ever seen.

Anyone who has ever done a maze will instantly recognize the conventions and be able to maniuplate them. Don't let that intuitiveness deceive you about how deep the game goes; there are more than 100 levels, each with its challenges. Some of those challenges are quite intense.

TOWER DEFENSE

One thing that many great games share is their ability to change a design idea without really changing it. That is to say, these games are able to innovate and seem fresh without ever straying from their core idea. GCL is able to do this with the tower defense genre. Amplification towers, traps, debuffs, moving towers between static positions, and meta-levels are not new. GCL has done two things well, here, however. All of these well-used features are fairly nuanced. The towers are well-varied, and with the ability to make hybrids, there is a fairly deep roster of tactical possibilities. Amplifying towers in particular have a considerable amount of strategy involved in choice, use, and cost effectiveness. These towers increase the damage and various special effects of adjacent firing towers. One amplifier can affect several different firing towers at once, although not at full strength. Divided amplification has a decent economy of scale; that is, it doesn't amplify 2 towers at 50% or 3 at 33%. Additionally, although a gem of any type will enhance damage, only gems of the same type will amplify the unique special effects like hitting multiple targets, slowing enemies, or depleting enemy armor.

The other thing that GCL has done very well is to set up game situations that force the player to a broad variety of tower defense strategies, rather than relying on one. One of the ways that the designers cause the players to change their strategy is by using accelerating costs. Every buildable structure except the gem itself costs progressively more than the last one built. So it's not possible to build a million towers, and simply move the gem between them again and again. The towers would get prohibitively expensive as more are built, especially when the place a player really needs to spend money is on his gems. This is doubly true of amplifiers, whose cost goes up markedly, so as to combat the relatively cheap cost of amplifying your firing gem with a number of basic gems. Traps and shrines operate much the same way, the effect being very pronounced on the latter.

ADJUSTABLE DIFFICULTY AXES

The player is given control of a number of different factors that enhance the difficulty of any given level of GCL. The upside of increased difficulty is that the end-of-battle rewards (in EXP) are increased significantly. Thus, it is always in the player's best interest to estimate the maximum winnable difficulty so as to maximize rewards. The adjustable factors are dissimilar enough that, depending on the player's style, there can be any number of combinations to maximize reward. Number of invading enemies, type of enemies, strength of enemies, penalty for allowing enemies to pass, enemy speed, and other factors are all added together and then act as a multiplier for the amount of experience the player receives upon success. Clever application will result in the ability to power-level in an exciting--and often necessary--way.

One very good peripheral aspect of the difficulty settings is that as the player levels up and is able to take on more difficulty, every single level (out of more than 100) will bear replay again and again. In many cases, it's absolutely necessary, although most levels feel very different the second or third time around, because of those dimensions of difficulty. Replays award experience in a "high score" fashion, where exceeding the previous high will net the player the difference in EXP, thus eliminating the possibility of rote grinding. I still played all the way to character level 114... so, whatever.

FUNGIBLE STATS

The player character gains levels with experience; these levels translate into skill-points that can be spent on a number of abilities that enhance the powers of certain gems, make gem costs cheaper, or increase the starting pools of resources. Every investment of level-up points is reversible, however. At the starting screen for each game level, the player is able to move these points around in any way they choose at no penalty. This is important, because for as many tactical situations as the game pushes you into, there are as many strategies to carry the player to victory.

CONCLUSION

GemCraft Labyrinth is an accessible, free online arcade game. Even if tower defense is not something you normally play, the way that the designers were able to make a number of well-used elements fresh all over again is worth seeing. This is a genre that's only going to get bigger, and it tends to highlight a lot of interesting game design ideas, which is great as far as the Forum is concerned.