Part 2: The Composite Era

The composite era of videogames began with Super Mario Bros in 1985. Super Mario Bros was the first proper example of what we can call a composite game. To put it simply, a composite game is a game in which a player can use the mechanics from one genre to solve the challenges from another genre. In Super Mario Bros, this generally manifests as players using platformer mechanics (controlled jumping) to solve action game problems (defeating enemies).

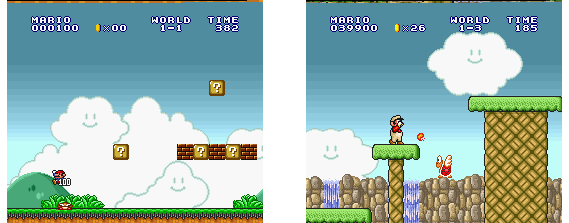

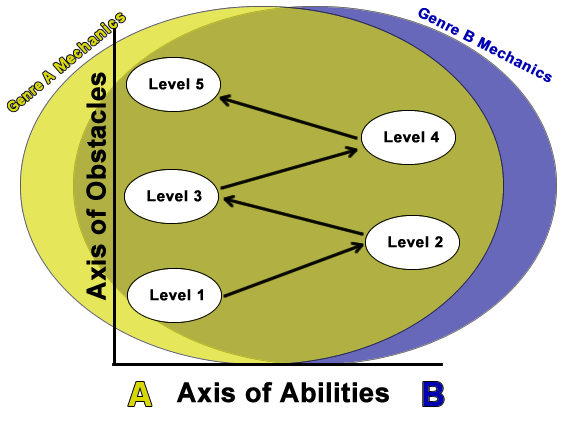

(Note that I use images from the SNES ports of the Mario games because that is what I own; the graphical changes don’t affect the design features I wish to illustrate.)

This genre composite goes two ways of course; sometimes the game offers the player action game solutions to platformer problems. A good example is the case above and right: using fireballs to take out obstructing enemies makes the platform target a lot easier to jump on, unimpeded. For the most part, every level in Super Mario Bros has both action and platform challenges for the players to tackle throughout, although each level tends to favor one of those genres more than the other.

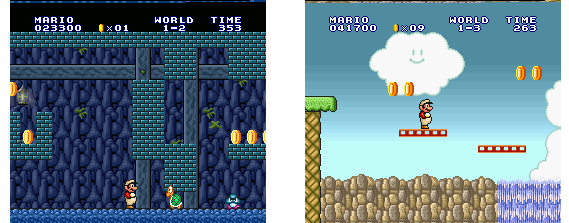

The elements of composite design are firmly rooted in the major design developments of the arcade era. The axis of obstacles and the axis of abilities are still present; in fact they’ve evolved and mean far more than they did in arcade games. For example, arcade games mostly only have one axis of obstacles, but composite games can be seen as having two or more. Because there are two or more groups of skills from different contributing genres, you can measure each group of skills on an axis as you would normally. From challenge to challenge, the difficulty curve we see is basically the same as the one from the arcade era, except that it’s bouncing between genres. Composite games tend to keep their gameplay interesting by avoiding the over-taxing of a single group of skills. That is to say, the player is never using one set of skills for long enough that he or she becomes bored with it. For example, World 1-2 in Super Mario Bros features more than twenty enemies and six deadly platform jumps (for which death is definitely the outcome if the player misses the landing).

The low ceilings and masses of enemies mean that the stage’s emphasis is on acquiring and using the fire flower. This is an example of how a change along the axis of abilities (via a power-up) can emphasize the game’s action elements. World 1-3, on the other hand (above, right), features less than ten enemies and sixteen deadly platform jumps; this is obviously a platform-oriented stage. Most of the enemies are located on (or drop from) platforms high above the player, so the fire flower isn’t as useful. This is a lateral movement along the axis of abilities that emphasizes the core platformer skills. Both stages are composed of mixed platformer and action challenges, but the focus of the design changes from level to level.

By shifting between skillsets just before players get bored, composite games are able to more easily induce a flow state in their players. The psychological state called flow is a kind of clear-minded euphoria that players experience when they’re totally locked into a game. Most players of videogames will recall having experienced times when they’re completely engrossed in play, and minutes or even hours disappear. It’s not just gamers that experience this; runners, knitters, musicians and plenty of other people can all experience the same thing when they’re locked into their respective tasks. Flow is a state of positive focus, and can have a wide variety of causes. Composite games are able to put players into a psychological state I call composite flow, which isn’t exactly the same thing, but is very close to ordinary psychological flow. These games can do it by using a structure like the one visualized here.

The difference here is that the flow is achieved not by getting the player to focus on one task, but by changing the player’s focus at exactly the right times. A well-designed composite game will shift between skillsets before a player starts to burn out and lose their flow, keeping the euphoric focus going for a very long time.

Two Types of Composite Game

In the next few years after Super Mario Bros, composite games exploded in popularity, both among players and among designers. It was clear to designers of the late 80s that by choosing their components wisely, they could build a huge variety of new games out of arcade-era ideas. Because of the influence of SMB, many of the classic franchises included platformer elements. Mega-Man, Contra and Metroid all combined platformer and shooter elements to create classic games.

Each of those games had a unique feel, but they were essentially the same kind of game at a fundamental level. This kind of game is a composite built on the conservation of controls. In other words, it’s relatively easy for designers to combine 2D platformers and shooters because they share many of the same controls inherently; the designers don’t have to add too much. In all of the games I listed above there’s a similar control scheme: d-pad to move, one button shoots and the other button jumps. Even if the platformer and shooter elements vary greatly, the controls can combine very intuitively and offer a deep. This means that the player isn’t bogged down in learning mechanics, but rather can focus on the larger features of the level design. On the other hand, we’ve all played games in which the controls had clunky features which were so counterintuitive as to be unusable. Or consider PC games that use dozens of buttons, for which it’s impossible to remember all of the functions. This is often a result of a composite whose genres didn’t work together. This isn’t to say that those games can’t be fun, because there are some games that have a million buttons and are terrific. Competitive multiplayer in the online era necessitates having lots of extra buttons, because competitive players are willing to go to great lengths to master convoluted control schemes in order to gain a competitive advantage. This doesn’t meant that there aren’t great competitive games that use elegantly combined controls, though—just look at classic fighting games. But in the realm of single player games, finding a way to combine controls intuitively is one of the most important tasks a game designer can take on. Some genres combine better than others.

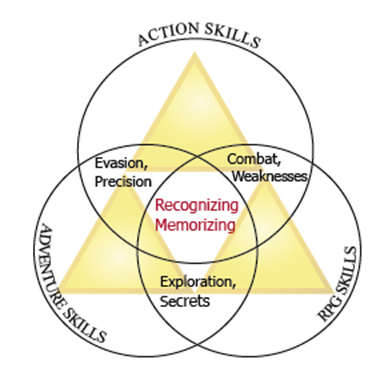

Intuitive hybrid controls aren’t a necessity for a good composite game. It’s also possible for a game to make a composite out of the more cerebral elements of game design. Game designers often build their composite games upon cognitive commonalities. This means that although the controls aren’t necessarily a mix of different genres, the mental skills involved in playing the game do involve a genre mix. This sounds vague because it refers to a huge range of games. There are some great examples from the early composite period that make the meaning clear, however. The best example is The Legend of Zelda; it’s a composite of action, adventure and RPG elements. In order to facilitate that combination, the player has to sometimes break the flow of the game by going into a slightly clunky menu. So while the controls in a game like Zelda are more practical than they are elegant, we can visualize the more cerebral common ground between them as being a Venn Diagram with three centers.

What the three games have in common is a cognitive skill: quickly recognizing and predicting patterns based on familiar cues. In action games, it’s important to recognize the patterns of enemies—especially bosses—in order to avoid their attacks and exploit their weak points. In adventure games, the player has to recognize the cues a dungeon provides for solving puzzles: for example, if there’s an unreachable platform with a target on it, you probably either need to use or find some kind of projectile. In RPGs, it’s necessary to notice patterned cues in enemies in order to exploit their elemental/weapon weaknesses, and necessary to recognize the cue that signals that there’s a secret door or hidden chest that could contain a powerful new item or heart container. Those extra hearts can really help players survive bosses—which is a great example of using RPG mechanics to solve action game problems. These aren’t the only skills from each of the respective genres in Zelda, but they are the common ground between the three contributing skillsets, and they make the game coherent and engaging.

The Proliferation of Composite Design

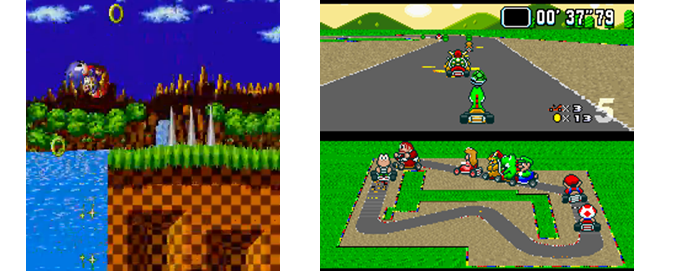

Whether they were using control composites or cognitive composites, designers from the late 80s and early 90s got a lot of mileage out of composite design techniques. Sonic the Hedgehog, for example, took the action/platform composite and added another genre to the mix: racing games. As long as the player uses precise racing-style reflexes to avoid obstacles like pitfalls and spikes, Sonic can gain momentum like a racecar, and launch off of large ramps in the terrain, soaring into the sky in a greatly embellished platform jump. This is used to solve platformer problems, as suddenly those out-of-reach platforms become accessible to the soaring hedgehog.

Or consider how Mario Kart so obviously lets players solve racing problems (trying to get to first place) by giving them lots of different shooter power-ups. Those red shells aren’t in the game for nothing! There are literally hundreds more examples of game designs that employ composite techniques, but listing them would take up too much space for this article—although we’ll see a few more examples shortly.

The obvious objection to this view of videogame design history is that it stifles creativity in game design. If designers are just dipping into the well of arcade games, combining them and releasing them as original products, there’s no reason for designers to ever come up with something truly novel. Composite games are great, but eventually the number of untried combinations is going to dwindle, and the market will become dull. This is a fair objection, and so next we’ll take a look at the later developments in composite games. Specifically we’ll look at how the early first person shooter and real time strategy titles used composite designs when inventing original genres that have stood the test of time.